Sachiyo Ito’s Memoir: Chapter 13

Sachiyo Ito continues her memoir on JapanCulture-NYC.com

Since January 2024 renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

St Louis Post-Dispatch August 29, 2014 - September 4, 2014

“NIHON BUYO – DANCE IS A MIRROR INTO JAPANESE CULTURE: Japanese Dance: Looking into Japanese Culture . . . In addition to viewing Japanese culture through the lens of dance, observers and dancers also learn about themselves and apply the valuable lessons learned on the dance floor to their own everyday, modern lives.”

New Year’s Greeting

Happy New Year!

May your 2025 be beautiful, creative, and healthy!

The 12th Chapter was about reflections and mirrors, and now in this chapter I would like to continue exploring the theme of “mirroring.”

Also, being the beginning of the year, let me also talk about our so-to-speak “New Year Greeting,” the Odori-zome, and about the significance of the greeting gesture, bowing in dance.

The phrase “dance is a mirror” has been the backbone of the philosophy behind my teaching and performance for the past fifty-five years in Japan and the world outside of it.

Dance reflects the culture that has nurtured the dance form. For all facets of the culture and arts such as history, literature, social life, geography, climate, and racial components are what has created the dance form, the art that is born in the particular culture and has been inherited for centuries. It is one of the best ways to communicate between peoples beyond barriers of culture, language, ethnicity, and races.

Over the years, this idea developed into a program, and I called it “Japanese Culture through Dance,” designed for schools and cultural institutions. I hoped to help students understand the culture of Japan through learning traditional dance forms. I have always believed that dance is an important tool to help young students broaden their horizons and learn to understand new and different cultures by learning their traditional dance forms, styles, and techniques. Ultimately, my goal is for students to reflect on the meanings of their own culture’s art forms compared to what they learn in our workshops and classes. Ideally, these educational experiences will act as a source of inspiration in their future creative lives.

Dance/NYC stated the role of dance eloquently in its August 2024 post: “Dance is not just an art form; it is a powerful means of expression, connection, and transformation. It bridges cultural divides, fosters empathy, and brings people together in a shared experience of joy and creativity…Dance has the unique ability to tell stories that words cannot fully capture.”

“Japanese Culture through Dance” has come to be called the “Free Children’s Workshop,” offered at libraries, schools, and cultural institutions. I originally thought this idea was only for youngsters, to open up their horizons, to allow them to get to know different parts of the world, and to better understand others in their local communities that come from different backgrounds. However, after giving workshops in senior centers and geriatric centers more and more in recent years, I began to realize that speaking about cultures through dance is important for the elderly too. Not only can they share their life experiences through watching and learning dance, but they share their own life stories, also. Those who attended our workshops at the senior centers happily told me stories that stirred up from their memories by dancing, which in turn evoked thoughts about their own culture, associated with Japanese experiences.

Considering that New York City is a melting pot of culture, my dancers and I were so happy to be part of the special concert series bringing various cultural traditions together to showcase in 2008. The occasion was Waves of Traditions held at Brookfield Place, the former World Financial Center building. The program honored the diverse ethnicities and cultures in New York. Our two showings on the day we performed were wonderful opportunities for us to display our repertoire of Japanese dance right by the Hudson River, appreciated by people who came to join us during their lunch break, while shopping, or after work. What a beautiful opportunity was it to dance in front of the Hudson River from the second rotunda! I will never forget watching the sunset over the Hudson through the windows while we tidied up and packed away our costumes and props. This led me to recall my performance at Windows on the World, the famed exclusive club and dining room at the top of the World Trade Center, a few years before 9/11. The view from there was one of the grandest sights I have ever seen, its memory made all the more poignant after the devastation and loss of 9/11.

As I consider my dance students, I think about the changes I have seen over the years, the different populations coming and going like waves. I remember my surprise when emergent Japanese hip-hop dancers began to receive awards in competitions such as the one at the Apollo Theater in the late ‘90s. From hip-hop young dancers in their 20s and 30s, to aspiring Broadway stars, to Japanese dancers traveling all the way from home in hopes of becoming professional performers, many people of all backgrounds have walked through my studio door. Their passion reminded me when I was young, though survival in New York, in both carrying out their mission and living, is tough.

Broadway shows were also becoming more and more attractive to aspiring Japanese artists, but they also realized how important it was to know their own cultural and traditional roots. I was so pleased with their decision to study Japanese dance, and I hoped it would inspire their own creative activities. Further, several of them were so dedicated to Japanese dance that they went on to become core members of my dance company.

Over the years, there has been a clear transition in the age of my studio’s students. In the early 2000s, boys and girls as young as three years old, whose parents felt it was necessary for their children to know their own traditions, came to study with me. Now, there are more seniors than children in my classes and at the workshops.

Since the pandemic, unfortunately, there has been a big decrease in the migration of young artists from Japan, whereas NYC senior centers’ workshops, during and post-Covid, have become much more prominent, which points to an obvious societal shift.

I miss children’s workshops, now that the schools and libraries where I used to work seem to give less importance to interaction with artists in workshop settings. I believe that hand-to-hand and eye-to-eye contact in teaching and learning are incredibly important. I do understand that educators have had to give more priority to working on tablets and with technology rather than focusing on in-person learning after the pandemic. However, to counterbalance that trend, I feel the arts should be even more important, to offset the isolating work of young ones on tablet screens. The arts can provide a unique sense of one “as an individual” in our AI age, that is uniquely human and humane.

Odori-zome

At the beginning of each year, I hold an Odori-zome, or New Year’s Dance. This event has been held for the past 25 years at Tenri Cultural Institute. The literal translation of the word “Odori-zome” is “to dance for the first time in the New Year,” and with this performance, we vow to study harder in the coming year. A similar word is used in calligraphy also, as in Kaki-zome: “writing for the first time.” This is the time for students to show the fruits of their studies over the previous year, and I find much pleasure in watching their progress and seeing their improvement year by year.

My students strive to demonstrate their best stage presence in this small public performance for friends and families. Some guests find it interesting to see my students’ various nationalities, as it is an international group, composed of people from different ethnic backgrounds who love Japanese culture: Chinese, European, Americans of all colors and creeds, as well as Japanese. I am so pleased that they experience no boundaries in their aspiration and love for Japanese culture and the arts.

As the Odori-zome is a significant event, the students must dress themselves in formal kimono. This poses a special challenge, as they are used to dressing in just a simple yukata. However, this special occasion motivates them to learn, often from video tutorials found online. I only help them a few times through teaching but emphasize that it is important to practice dressing on their own. If we are dependent on someone to help us, like professional kimono dressers, we will never become better at dressing ourselves. This is a valuable lesson for other parts of our lives as well. “You got to do it as you got to do it!” as my neighbor says. And you can do it.

Dressing for the Odori-zome is also a great opportunity to appreciate the beauty of the various types of kimono, such as tomesode and homongi, and the beautiful belts worn with them, such as maru-obi and fukuro-obi. During the post-performance party, as the students mingle with the audience, drinking and eating, the kimono they wear heightens the awareness that acquiring the art of moving gracefully is as important as in life as it is in dance.

In the interview I did for Chopsticks, cited at the beginning of this chapter, the writer talks about the graceful gestures and manners that the students learn during lessons which can then be applied to their day-to-day lives. That is what I stress as a teacher. We can apply graceful moves that we learn through dance training to our daily life activities and special occasions.

The New Year Dance has the significance of being a “greeting” in the New Year, but it has more meaning than simply saying “hello!” It is an acknowledgement of each other, a looking forward to renewal, an expressing of respect for others and all beings, and a showing of reverence to nature, which surrounds and protects us.

At the end of our dancing at the Odori-zome, we take a bow. This expresses gratitude, thanking the audience for watching the dance, as we consider the dance itself to be an offering to the audience, not a showing off of oneself.

Odori-zome 2016

Odori-zome 2016

Odori-zome 2023 - Photo by Tony Sahara

Odori-zome 2025 - Photo by Jon Jung

Odori-zome 2025 - Photo by Jon Jung

The Bow: Entering Sacred Space

“Sacred Traditions Meet Art in Traditional Dancing:

Each class starts with a short bowing ceremony where both teacher and students greet and hope to learn communication from each other.”

We begin dance lessons with a formal bow. How to bow properly is the first lesson I teach in workshops and in the first class for beginners. The bow is essential in learning Japanese traditional arts, including martial arts. We also take a bow at the end, expressing thankfulness of sharing what we learn in the class to classmates and teacher.

After kneeling, we first place a closed dance fan on the floor in front of us. My personal interpretation of this gesture is that the fan symbolizes one line, a line that divides our space into two worlds. The two worlds are the world of illusion—the theater—and the world of the surface—reality. I believe it is important that we are aware that we enter a sacred time and space of creation while learning dance. As a dancer and a teacher, I must say that the bow is far more than a simple greeting. It is “a dance” with form, rhythm, and meaning.

As for the form, we keep our spine nice and straight. And for the rhythm, we take at least one breath, in and out, giving us a moment to pause and reflect on respect. As for meaning, we show respect to the teacher, to dance’s heritage and tradition, to the colleagues with whom you share precious time in class. If a student accomplishes a beautiful bow in a workshop, it can be considered a successful participation. Now that I have more group lessons than private lessons, I find it very meaningful for the students to bow to each other at the beginning and end of lessons because we learn from each other by sharing the class time. I believe those shared moments become valuable lessons, not only in dance, but in many other ways.

Indeed, teaching has led me to discover the worlds of my students; their beautiful eyes, filled with a curiosity that I hope they never lose, will always be reflected within my dancing, and within my own heart.

Wishing you a season of inspiration and new discoveries!

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

Sachiyo Ito’s Memoir: Chapter 12

In 2024 renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

REFLECTIONS

With the time of reflection upon us, I realize there are many types of reflections, from mental contemplations to physical reflections. I would like to explore a few of them, not only because it's the closing time of the year, but also because I wish to announce the upcoming subjects of my memoir in the new year.

Although not an elaboration on a reflection of the year 2024, this chapter will be a reflection on oneself and then on the universe that surrounds us.

Tsuki no Akari Wa Shimiwatari

In 2005, for the 50th anniversary concert of my dance debut, I created a dance entitled Tsuki no Akari Wa Shimiwatari (The Moonlight Penetrates Through), using music with the same title by Himekami.

Placing the moon image high above the stage, my hand gestures focused on mirroring myself as if using two mirrors, one in front and one in back. Then, I used hands to symbolize the two human beings in the story of the dance. Just as important as the hands were the shadows reflected on the stage floor, from time to time with one shadow overlapping the other. The shadows, the ephemerals you cannot possibly capture, were all needed to tell the drama of the dance.

During the 1950s at the dance studio of my childhood teacher, there was no mirror. My teacher’s thought was that you should not be watching yourself dancing. According to her, to be conscious of your reflection in the mirror was not a good idea. I understood then that watching is a mental process, and so such intellectual activity is not dancing. This led me to discover what I consider the ideal state of performance. The best performance is when you are not conscious of yourself: You forget yourself, forget that you are the dancer. For me, the best performance is when I am not aware of myself, but I am just being in the dance, the body moving without thinking, without being dictated to even by the melody and rhythm. For your own body knows them. No mirror, no reflection of oneself is to be found here.

However, if we go back in Japanese history, we find a contradictory theory advocated by Zeami, the 14th century dramatist. He calls his theory “Riken no Ken” (“Viewing Oneself as Distant View”). It espouses an objective view: to be conscious of oneself analyzing one’s own performance. Can these two idealistic states co-exist?

Or perhaps he was talking about an even larger framework, that of the universe, and us under the stars, the moon, and sun. I wonder if we can step back while dancing, observe ourselves from all-encompassing angles, with the universe itself acting as our mirror?

宇宙よりおのれを見よと

いにしえの釈迦、

キリストもあはれ教えきLook at yourself from the universe, just as taught by Buddha and Christ.

— 窪田空穂 Utsuho Kubota

Kubota’s haiku above shares his deep insight: Look at yourself as a part of, or from a bird’s-eye view of, the universe.

In contrast to the universe, humanity is so small, a tiny entity in the immeasurable universe that makes me feel faint, and our existence and the drama we create in our lives seems so small. Indeed, we are nothing but a speck of dust, even less than a speck of dust. { }

But often our dramas become so huge and tremendous, more than we can manage with our emotions. Then, here comes a question: Are we real, or in a dream, or nothing but dust? Are we watching shadows only, shadows we cannot possibly capture and hold, as in my dance?

Actually, here is another view we can explore. There is each individual’s unique universe that reflects himself, while on the other hand there is the universe that contains all that surrounds us, the whole of existence. The universe is composed of experiences, encounters, nature, smiles of children, my dog’s happy bark, the sun, the moon, and water. The universe is what nourishes us and what watches us. Will it expand year by year, or by the experiences we gain, or by what we learn? I ask myself, “Is that a beautiful one, the universe that reflects me?” Oh, I doubt that... But how could a universe so rich in stories and lovely moments be anything but beautiful?

After many years of creation, The Moonlight Penetrates Through comes to my mind as a new lens through which to view the end-of-year installment of my memoir: the hands, the mirrors, the reflection of myself, the other human beings, many other beings, the sentient and the non-sentient, and then the universe itself.

Now, take a big breath in and out. With a smile, let us welcome our new universe.

Wishing you all the brightest and most beautiful 2025!

Postscript

Sachiyo Ito will return with further chapters of her memoir in 2025, when she will discuss dance as a mirror reflecting culture, the backbone of her belief in dance for more than sixty years.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

Sachiyo Ito’s Memoir: Chapter 11

Chieko Genso — Photo by Ray Smith

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

Poetry in Motion for the Time of Contemplation

Please Call Me by My True Names

In my memory, the bright morning sunlight during the walking meditation along the cliff over the Pacific Ocean was sublimely beautiful. In my mind’s eye, I look up at Rev. Hanh’s face as we walk up the hill, the brilliant sun shining behind him. Nowadays, this image returns to me on my morning walks with Joy, my dog. I must say it was the stroke of luck of a lifetime that I was able to meet Thich Nhat Hanh—the Zen monk, poet, and peace activist recommended for a Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1967—and get to know his teachings.

My first retreat with Thich Nhat Hanh and his sangha was in 1990 at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Although I am not a Buddhist, his teachings and poems have greatly influenced my work. It was he who inspired me to begin choreographing dances to poetry, which I began to do from then on. It was at this retreat that I also met Sister Chan Khong, a longtime associate of Rev. Hanh’s. She was kind enough to set aside time to meet with me so that I could show her the dances I choreographed and gain approval to show them publicly. Happily, this permission was granted.

I presented dances based on Rev. Hanh’s poems for the first time at my concert Dedicated to World Peace in 1991 at the Clark Studio Theater at Lincoln Center.

The main poem I choreographed for the concert was Please Call Me by My True Names, which appeals to the interconnectedness of all beings, both sentient and insentient. I titled my dance, though, An Invitation to Bell. The title may sound strange, but my intention was to ring the bell in a gentle manner, rather than by striking it, and to invite people to listen to the sound of the bell. The bell would signal the start of an interactive walking meditation, a time for us to pause and focus on breathing.

Through audience participation in the walking meditation, I hoped that Thich Nhat Hanh's call for humanism was heard and felt. I titled the concert Dedicated to the World Peace to reflect Hanh’s message calling for compassion, reconciliation, and inner harmony and held it on the weekend celebrating Martin Luther King Jr., who supported Hanh’s work.

Although the theme of the concert was sweeping and grand, one small, very human moment stands out to me. The Clark Studio Theater was small with a capacity of 100, but well equipped with lights and a high ceiling, which made set designer Bob Mitchell’s magical ball descending onto my hand possible in the piece “Moon Child.” For the stage set of Please Call Me by My True Names, I had to bring bamboo sticks, more than eight feet long, that would hold scrims across the stage horizontally and vertically. It was quite a trip to carry them from the shop to the theater. Somehow, I got them into the subway train!

Looking back on it now, I think that world peace was too big a subject for only a minor dancer to advocate for.

Spoken Poetry

Then I had the good fortune to meet Kim Rosen, who performs spoken word poetry, and Jami Sieber, a cellist, and collaborate with them for the 15th Anniversary Concert of Salon Series in 2013. I met them at one of the retreats they were offering, and a few years later I invited them to the concert. Luckily, they were able to combine an East Coast visit with their tour schedule and were able to participate.

I was used to poems, when spoken aloud, being referred to as “recitations.” Kim did not call her work “recited,” but rather “spoken” – “spoken poetry.” She would memorize poems and speak in a very moving manner, powerful enough to send us listeners into tears. With Jami’s cello providing a beautiful accompaniment, Kim’s speaking was deeply touching. Together, they offer workshops for healing around the country.

Thereafter, I presented a series of choreographies to recited or spoken poems.

In 2010 I presented “Poetry in Motion” at Joyce Soho, based on poetry including not only Hanh, but those of others as well: Neruda, Mary Oliver, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Rumi. These dances were accompanied by percussionists Yukio Tsuji and Egil Rostad. Singers Beth Griffith and Elizabeth Knauer recited the poems, including my favorite Chieko-sho, which you may remember from previous chapters. The poem Only Breath by Rumi inspired me for its cross-cultural work where the human spirit gathers as one. Different ethnic dance forms represented cultures across the world, including Indian, Russian, ballet, and contemporary dance. To represent Japan, I chose a karate master, Tokumitsu Shibata, who impressed both artists and the audience as he combined karate with my choreographed movements so well that it was simply amazing. The concert was one of the most exciting collaborations of my career.

Photo by Reiko Kawashima

Photo by Reiko Kawashima

Renku and Dance

Inspired by the teaching and poetry of Rev. Hanh, I began a work combining haiku, walking meditation, and dance. Walking meditation requires quieting and focusing the mind, which also helps in both the composition of haiku and the creation of dance. I began presenting this as a workshop at spiritual retreats, such as Dai Bosatsu Zendo.

The most memorable venue where I gave this workshop was the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens in Florida, where I had been previously invited to perform Japanese dance at local art galleries as well as Delray College.

“Ito danced to a haiku written by suburban Delray Beach resident Douglas Davy.

’She was very deliberate,’ he said. ‘You could watch a performance, but it’s taking something written and interpreting it . . . It was extraordinary.’”

By my third visit to the Museum in 2002, the facility had been beautifully renovated, including the addition of a Japanese garden. My program was titled “Walking Meditation, Poetry, and Dance.” I conducted the walking meditation for participants in the auditorium, then continuing into the outdoors and around the garden; this stroll would serve as the basis for the haiku composed later. Upon returning to the theater in the museum, I improvised dances to the haiku stanzas presented by the audience. The pine trees in the Japanese garden were just as magnificent as those we see in Japan and proved to be very inspiring for the composition of haiku. The breeze through the pines was so lovely that it brought to mind the line, “Rustles of the wind, or whispers of the pines…” from the Noh play Matsukaze (Pine Wind).

In 2003, the program An Evening of Renku and Dance, held at Japan Society in collaboration with the Northwest Conference of Haiku Society of America, was the beginning of my collaboration with Haiku Society of America. Six poets, along with three musicians and I, were on stage, ready to improvise on whatever haiku the poets might compose. We concluded the program with a haiku from a member of the audience. It was a humorous one, written by a lady from India, about a bug in the head! And so, my dance was humorous as well. After the performance, she gave me a beautiful red silk Indian scarf, a gift I cherished for many years. I was happy and perhaps a little relieved as the program ended with a lot of smiles.

The collaboration with Haiku Society of America did not end at the Japan Society concert in 2003, but continued through 2023 in my Salon Series, led by Penny Harter, John Stevenson, and the late William Higginson.

To collaborate with me on linking renku and dances requires the ability to write haiku on the spur of the moment while watching my dance. For this improvisation of dance and stanzas, spontaneity is the essence of the endeavor, rather than contemplation. It requires a genius to write a stanza on the spot, making a quick decision on the choice of words upon observation of the dance. I must bow to all three poets, who so effortlessly showcased this skill. Bill was a prolific writer, instrumental in introducing haiku to the Western world, while his wife, Penny, was more than a haiku poet. Although their penmanship is unbelievably prestigious, they were incredibly kind and generous in supporting my work and collaborating with me on Renku and Dance in my Salon Series. As for John, he has been with me all these years, a partner in words and footsteps. My gratitude to him and my respect to his haiku and scholarship as a writer, thinker, and poet is more than I can express. His haiku is often humorous, yet it has a deep, humane touch. His essay in my Salon program on the theme of resonancewas incredibly insightful:

“There is no meaning to light without darkness, no meaning to darkness without light. Conflict, however, is not the only way of looking at these mutually dependent aspects of reality. A great deal of their interaction is characterized by harmony and resonance.”

One of my favorite haiku by John, chosen from among far too many, is this:

A deep gorge...

Some of the silence

is me— John Stevenson

Geppo, July/August 1996

John would gather his friends from the Haiku Society of America for my programs and come down from Ithaca, where he lives, by train for the day to join the program. Hence, our Renku and Dance were held several times across the decades of the Salon Series and featured in the Salon Series finale as well. I was so pleased that John could join us for the final program.

Renku and Dance inspired the workshop Dance and Poetry of Japan, held at senior centers in Chelsea and the West Village in New York. Participated in by seniors who love poetry or Japanese arts and culture, the program has been repeated for the past four years. The seniors are great composers of haiku, and they bravely answer the challenge to make Japanese dances based on haiku and renku. Together, we share our life stories, inspired by our poetry composing process and dancing. We converse about our histories, the countries we come from, and through the poetry we create, we find ties that connect us across ethnicity and culture, rather than boundaries that separate us. Together, we come up with new dances to illustrate our poems. Watching the seniors learn new forms of dance is simply amazing. I call them seniors, but their interest and curiosity keep them young at heart, which is a valuable lesson for us all. The ephemeral quality that is shared by poetry and dance, particularly Japanese dance with its subtle evocativeness and suggestiveness, gives us a vast possibility of expression, of ways to tell the stories of our lives. It is something I am thankful to have discovered in my life.

Listening to Sand

pouring sand

from one palm to the other— she listens

foam slips

from a clam shell, sand draining with it

carried out above

the sea, sand drops from a gull's cry

at the sea's edge her feet slap the sand-breaking waves

listening to sand she remembers night wind—

dune grasses yielding— Penny Harter for Sachiyo Ito, written during her dance to Chieko: The Elements (Chieko: Genso)

Copyright © 2008 Penny Harter

Chieko Genso — Photo by Ray Smith

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: CHAPTER 10

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

The Cranes

“Yume (Dream), the closing piece for this program, is a remarkable signature piece for Ms. Ito’s dancing and acting. It is a poem in movement and truly shows the wide range of Ms. Ito’s knowledge and abilities.”

In Chapters 6 and 7, I explored the theme of transformation through dance. In Chapter 7, I discussed a transformation from a beautiful being into an ugly one: the lovely maiden turning into a hideous snake in the Dojoji story. But what about transformations going the other way, from the mundane to the ephemeral – like in a dream, where you trade your arms for wings and fly?

Birds hold a universal fascination for mankind. They are depicted in poetry, painting, and song across cultures. We watch them in their migrations, knowing as they fly overhead that the season is about to change. In the West, the official bird of October is the swan. In Japan, the birds that represent elegance and quintessential beauty are also waterfowl: the tsuru (crane) and sagi (heron). They are highly valued for their purity of color and the graceful sweep of their wings in flight. Another bird that is prevalent in Japanese art is the white-fronted goose, often depicted flying through the skies of autumnal paintings.

In the Kabuki dance Azuma Hakkei (The Eight Beauties in the East), geese become messengers of love when a character in the dance entrusts them with his love letter. What an enchanting idea it is! In another Kabuki dance, Fuji Musume (Wisteria Maiden), geese play an important role. At the end of the dance, the lyrics of the music describe the flight of the geese in the twilight sky:

空も霞の夕照りに

名残惜しむ帰る雁がねThe sky is hazy and the evening light is glowing,

the geese return home reluctantly.

We are left with a lovely and memorable image, an appropriate farewell to the end of the dance. The words “returning geese” make me wonder where they are going as I raise a hand to view them. Is this gesture a metaphor for two lovers returning to their home?

Hiroshige ukiyo-e painting in Omi Hakkei

As I child, I used to dream of flying. I was not transformed into a winged bird, but into Ten’nyo, the angelic figure depicted on the ceiling of Todai-ji Temple in Nara. There are many ways to analyze the psychology of flying dreams, but the only premise that resonates with me is that of freedom.

When I was young, I did not carry the pressures and worries that I do as an adult. My subconscious, unencumbered by responsibilities, must have taken flight very easily. Since then, I have loved “the flying in dancing,” whether classical, Kabuki dances, or my own works.

I choreographed flight in Chieko: The Element, the dance I created based on the work Chieko-sho (Collection of Poems for Chieko) by Kotaro Takamura. In one of the poems in the collection, “Lemon Elegy,” there is a line: “Chieko flies!” I had my singers sing this in a high-pitched voice, almost like an exclamation. In Chieko’s case, flying was a metaphor for leaping into a realm of insanity. I envisioned my own movements as that of a white bird, flying into the black space beyond the stage, the darkness of the theater becoming a spiritual world separated from reality. I believe that Kotaro wanted to express that Chieko found release from the worries and responsibilities she carried as a woman, wife, and artist in her flight. In doing so, he placed her on an eternal pedestal; in another poem, he expressed, “Chie-san, you are young forever.”

Other expressions of emancipation can be found in dances and plays in the genre of Kyoran-mono (the insanity pieces) in Kabuki plays, in which the protagonist loses his mind. My favorite is Onatsu Kyoran (Onatsu the Insane), the famous work created by Tsubouchi Shoyo in 1914. I performed it at Pace University Theater in 2004. This performance was a dream come true for me. Not only was I able to invite Shogo Fujima, a renowned dancer, to come to New York from Japan as a guest artist, but I was able to rent the exact same costumes from the original production from the Shochiku Kabuki Costume Shop.

While the portrayal of an insane character may suggest frenzy and ugliness in Western theater, in Japanese classical theater, an otherworldly, ephemeral beauty is a hallmark of insanity. I often think that we dancers are very fortunate to be able to transform ourselves into such characters.

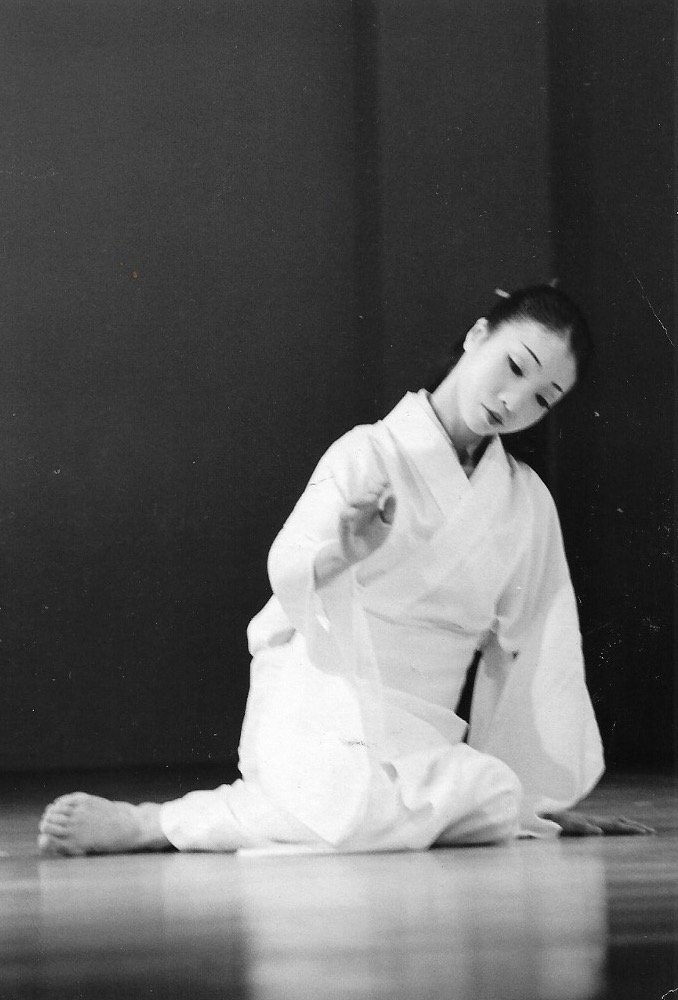

Sagi Musume (The Heron Maiden) at Mitsukoshi Theater, Tokyo

The first Kabuki dance I performed that was inspired by birds was Sagi Musume (The Heron Maiden) at Mitsukoshi Theater in Tokyo in 1968. Beloved from its first presentation in 1761, Sagi Musume has been recreated many times. The mystery of whether the heroine is a woman or a heron unfolds as she moves from joy to despair, before suffering her final fate in Hell. The white color of the heron suggests the innocence of a young lady before she experiences the turbulent emotions of a love affair, while the snow functions as a metaphor for both purity and the fleetingness of love as it melts away. The weight of the heroine’s thoughts is reflected in the heaviness of the snowfall, amplifying the drama of the Hell scene at the end, as the snow falls on the suffering heron. Since then, I have performed this piece numerous times in the U.S., and the long white sleeves and trailing hem of the costume have turned gray from brushing the floors of so many stages.

Performing Sagi Musume for Japan Society. Photo by Thomas Haar

My first original work with birds as a theme was Crane, which I presented at the 25th anniversary concert celebrating my American debut. This dance was inspired by one of my greatest supporter’s love for the red-crowned crane, one of Japan’s most beloved animals. I met Mary Griggs Burke at the celebration of her 75th birthday in 1991, which also commemorated her acquisition of a painting of a scene from Ibaraki, a well-known dance drama in Noh and Kabuki.

With Mrs. Burke at the post-performance reception of the 25th anniversary concert in 1997

The theme of the painting was a transformation of an old woman to a demon, so I created an infernal dance, accompanied by two dancers from my company. I had fractured my foot a few days before the performance, but knowing that the show must go on, I danced regardless and did not let anyone know of my injury until after the evening was over. You can imagine Mrs. Burke’s surprise when she found out after the party.

Crane. Photo by Kathy Sturgeon

Over the following years, Mrs. Burke’s support for my work was very important. After the 25th anniversary concert, held at Florence Gould Hall in 1997, she held a very special reception and tea ceremony at her residence for my guests.

Mrs. Burke was also a supporter of both the International Crane Foundation in the U.S. and the Japanese Crane Foundation. With her love of these beautiful birds combined with her love of Japanese art, she amassed a fabulous collection of screens depicting cranes from the Edo era, created by artists in the Rinpa school of painting.

When the International Crane Foundation in Wisconsin held a celebration for her 80th birthday in 1996, I was invited. I was thrilled to create another crane dance, this time based on the folktale Yuzuru (Twilight Crane). It was a magical evening. I had a special crane costume made with one white, sheer sleeve designed in the shape of a wing. In the story, the heroine first appears as a woman, although her true form is a crane. In the end, she returns to her avian form. I wanted to represent the character’s half-humanness to the audience with the sleeves’ one wing – to capture the essence of being caught between two worlds. The entire outdoor stage was dark but for a single bright streak of light. I felt as if I were entering a void in the darkness of that space, about to step into an infinite universe at the end of the dance.

Two decades later, in the installment of the Salon Series that introduced Japanese folk tales, I choreographed another Twilight Crane, accompanied by a flute and an ancient koto. Inspired by a Chinese Opera costume, I had the special sleeves designed as wings for my costume. I also invited a weaver to the program. After giving a demonstration of weaving on her loom, the same type used by the crane in the story, she became a part of the performance by being cast as a shadow. In the original tale, the crane, living as a human, secretly pulls out her feathers to make a beautiful fabric that her husband can sell in the market. I was very fortunate to be able to borrow the weaver’s piece of fabric to use as that woven by the crane. At the end of the piece, the wing-sleeves became large as I spread them, affecting a farewell gesture as the heroine departs the earth, abandoning her life as a human to return to her true form as a crane.

In 2008, I created a dance of cranes for a trio set to a modern koto composition by Sawai Tadao, Tori no Yohni (Just Like Birds), for dance students at Stephens College, where I was a visiting professor. These pieces were choreographed in a contemporary rather than a classical style. I was extremely happy with the result as the students, all trained ballet and modern dancers, performed so beautifully. It was also a lot of fun to go to local stores and choose fabric for costumes with the director of the costume department. I was very lucky to be invited to teach at a college that has such well-established and longstanding theater and dance departments. They make every effort to create the best college production possible and present them with great pride.

One of my most poignant performances came in October 2020. Salon Series No. 67: Prayer for Healing and Peace once more featured cranes as the central theme. In Japan, cranes are the symbol of longevity, healing, and happiness. Over the course of that spring and summer, we had watched the world come to a halt, overcome by disease. In spite of the pandemic, I decided to present the program. Of course, the circumstances of the lockdown necessitated that the performance had to be livestreamed, a first for my company.

As a prayer for the victims of COVID, I offered the dances Dedication, and Seiten no Tsuru (Cranes in the Blue Sky), performed by two of my dancers and me. The program also featured an origami demonstration by Colin McNally, whom I met during my Free Children’s Workshop program. Among the schools where I gave workshops in 2019 was the Beginning with Children Charter School in Brooklyn, where I taught Mr. McNally’s students. In 2020, hearing that he and his class had completed the senbazuru project, or one thousand folded paper cranes, I invited him to participate in the Salon Series program. Folding one thousand paper cranes has come to invoke well wishes of healing and recovery for those who are ill.

Mr. McNally was happy to talk about his senbazuru project for cancer survivors, and he showed us how to fold a paper crane. I also discussed twelve-year-old Sadako Sasaki, who famously set out to fold one thousand cranes after being diagnosed with leukemia as a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Her memorial at Hiroshima Peace Park is now covered with paper cranes from around the world. The program ended with my friend and guest artist Beth Griffith, a wonderful singer and actor, singing “Amazing Grace” as a light to guide our healing in the darkness of the pandemic.

Like the birds, we perform migrations of our own over the course of our lives – evolving from carefree dreamers to responsible adults who light the way for those who come after us. My journey began as my dream, then dancing as a crane, then evolving to a Salon Series, Prayers and Healing though Symbolism of Cranes. Was it a long flight, you might ask? Actually, it was a quick trip for seventy years – almost like being in a dream.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: CHAPTER 9

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

Rocky’s Kabuki to Montevideo

During my career, I was privileged to perform extensively beyond New York and the United States to other parts of the globe.

For the month of September, as we embrace autumn transitions to new opportunities, exciting times at school, and new friendships, I would like to share with you in Chapter 9 these treasured experiences and encounters that have touched my heart and strengthened my mission.

Kabuki in the American West

“Rocky’s Kabuki” was the eye-catching title of the article in the Billings Gazette announcing my performance at Rocky Mountain College in Montana in 1985. It illustrated how rarely Kabuki and Kabuki dances were seen in the West. Of course, even in New York City during the 1970s when I began performing, Kabuki and Kabuki dances were still a little-known theater and dance form.

My tour of the American West, covering the states of Montana, Idaho, and Arizona, was sponsored by The Institute for Studies in the Humanities in Ogden, Utah, and supported by the Asia Society and Japan-US Friendship Commission. The Director of the Institute, Dr. Carol Browning, accompanied me throughout the tour. The colleges I visited were Rocky Mountain College in Billings, College of Great Falls in Great Falls, Carroll College in Helena, the College of Idaho in Caldwell, Northwest Nazarene College in Nampa, and Grand Canyon College in Phoenix. In all of these places, the staff did their best to accommodate my requests to make the performance possible: things such as having an assistant in the dressing room and cleaning the stage. Even with their enthusiastic help, I wound up performing what I called the “Mop Dance” – the school auditoriums were so dirty that the hems of my kimono, as they trailed along the stage floor, became as soiled as a mop! I remember that at one of the colleges, a staff member was cleaning the floor with an old mop while wearing his outside shoes. He beamed a huge smile at me as he cleaned and said, “You can see I’ve cleaned it nicely for you!” I could only smile in return and thank him while I wondered to myself if I could afford to have the Wisteria Maiden costume remade for me by the Shochiku Kabuki Costume Shop in Tokyo. It was very worrying, for Kabuki costumes are dreadfully expensive, and I thought that the hem would wind up ruined.

It is well known that the Japanese take their shoes off upon entering a house, as a sense of cleanliness is an important element in Japanese culture. It is less known that in the traditional theater, the stage is considered to be sacred; for our dance, music, and drama began as offerings to divinity, and so the stage must be especially clean, pure, and pristine. Experiencing the cavalier way Americans treat their stages was something of a shock.

Before the tour, I had thought my performances were meant only for the students and professors on campus, but it turned out that the entire community in the areas of these states was invited. It was so wonderful to exchange conversations with so many people from so many different walks of life! It was very nice to talk to those who had visited Japan and would love to go there again.

Although the art form was unfamiliar to them, I must say that those who attended my performances in the West, both students and from the community, were all very patient as they waited through the several costume changes during the performance. I hope that they at least found the narration about Japanese dance and culture in between each dance informative enough to make up for the waits!

Genius and Genesis in Kabuki Show

“To see Ito dance is to be transported across time and distance, and to become a witness to centuries of precision in drama and movement.”

— Peter Fox, Billings Gazette Regional Editor (Review at College of Great Falls), 1985

Introduction to Germans: Bonn International Tanz Workshop

“Sachiyo Ito proved herself to be a master of the Noh and Kabuki dance forms and the illusive beauty and poetry of these over-400-hundred-year-old art forms…Miss Ito garnered warm applause for this guided glimpse into Fairyland.”

In 1983 my travels took me to Germany to host a workshop for two weeks. The workshop, directed by Fred Traguth, was kicked off with a performance, which was the most challenging aspect of the entire trip, since I had not slept for over twenty-four hours as I flew to the city of Bonn. The two-week workshop turned out to be a great experience for me, though. One of the things that impressed me was the students’ attentiveness to details: They followed all instructions very carefully. They paid very close attention as I taught them how to fold kimono, and they all learned it perfectly after only one demonstration! The Germans I met were immaculate, precise, and orderly, but they loved to have fun, too. My new friends all loved wine, which surprised me, because most Japanese people think that beer is the German drink of choice.

Alaska and Touring with AllNations Dance Company

Sachiyo Ito told a story of Urashima in dance... For many it was the first opportunity to see Japanese dances and understood why less is more . . . Hiroshige print come to life!”

— Judith Boothby, Dance Magazine, April 1975

From 1973 through the mid-80s, I toured with AllNations Dance Company. AllNations was directed by Herman Rottenberg, a lifelong board member of the International House at Columbia University. Herman, or “HR” as we lovingly called him, and Chuck, our beloved stage manager, were the backbones of the company. Dancers, director, and stage manager worked together seamlessly, and we made a great team. There are so many memories that I cherish from my days touring with them.

I have already shared a couple of stories from the AllNations tours, but there are many others. In Alaska, we performed in Anchorage, the state’s most populous city. We also performed in small towns such as Kodiak and Sitka, where we were treated to a special dinner of moose burgers! The fact that the burgers were made of moose meat was not the only thing we found surprising – the sheer amount of them was amazing. We were served a huge pile of burgers, nearly four feet high. It looked to me to be a Christmas tree made out of burgers! Our hosts thought that dancers were big eaters, since dance is so physically challenging, and we received the meal with deep gratitude.

The AllNations tour was not the only time I visited Alaska. I had given a solo performance at the University of Alaska at Anchorage, and a board member of the Anchorage School District invited me to give workshops in several schools as a resident artist for three weeks. I was given a small house during the residency, which was the smallest I have ever seen, but it came equipped with a garage. Everyone in Alaska told me to come during the summer, when the weather was so nice, but the way the timing worked out, the residency took place in January, in the depths of winter. I had never experienced before such cold temperatures and such dark days. While I was there, the temperature got as low as minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit. Every morning at 8:00 a.m. I was picked up to go to school, and I arrived home by 4:00 p.m. It was dark when I left the house, and it was dark when I returned. It was easy for me to understand the high rate of depression in the state, but seeing the bright smiles of my students every morning brought back the feeling of sunshine and made me very happy! I was impressed by how well Alaskans handled the cold and the dark, but I was also impressed by how well they handled the snow. Making a trip to the grocery store was an almost unimaginable experience. There was so much snow, and I had to shovel it all to keep the garage and driveway clear. It was the first time I had had to shovel snow in my life – you see, I am a city girl from Tokyo. Not knowing how to shovel snow, I wound up with my first-ever backache. Upon my return to New York, I had to see a chiropractor and spent everything I earned on medical treatment.

While touring with AllNations, I never had to shovel snow, and for that I was very thankful! However, that didn’t mean that there were not any problems. In one chaotic incident, some of our luggage was lost as we flew between cities. Unfortunately, this luggage contained the costumes for our performances. Thinking fast, we changed the program and improvised a few things to ensure that the performance would be on time and smooth. With only a few minutes to go before the curtain rose, we were feeling proud of ourselves for our grace and composure under pressure. Suddenly, the luggage arrived, and we switched back to our original performance plan! Even though the performance was saved by the timely arrival of our costumes, we learned a valuable lesson about adapting quickly to unexpected circumstances.

Speaking of unexpected circumstances: One year, our tour stopped in Maine in the middle of spring. It was late enough in the year that our hotel didn’t have heat. This wasn’t a problem except that during our visit, it became unusually cold. When we went to sleep at night, we had to put our costumes over ourselves to keep warm. Costumes to the rescue once more.

After Alaska, the cold couldn’t dampen my spirits, but being spotted by an immigration officer in Portland did. I was buying stamps at the local post office when the officer started to question me. He escorted me back to our hotel to check my ID and the performance permit, which was held by our stage manager. Everything was fine, but it was quite scary to be questioned by a government official. In the end, though, our trip to Maine was a very positive one. The incident with the immigration officer can never spoil my memories of Maine’s incredible natural beauty, especially one of a lovely rainbow over the rocks and waves at Bar Harbor.

In Urashima, the dance mentioned in the review above, you need to toss and catch fans; it’s a very tricky move. There is a film of the Kabuki dance Momiji-gari (Maple Leaf Hunting), performed by Ichikawa Danjuro the 9th, the legendary Kabuki actor. During the filming he dropped the fans but didn’t want to reshoot the footage. He expressed that the successful tossing and catching of the fans is not as critical to a performance as one might think, since there is much more to the art of dance than performing a successful maneuver. In all my performances of Urashima, I had never dropped the fans. Not in Maine, not at Japan Society, and not during my Salon Series performances – until this past January, when I missed catching them during my performance at the annual New Year’s Dance Party which I host for my students. Although we know that showing off is not good, we still want to succeed in our endeavors, particularly as we are not the great Danjuro.

We were so young and fearless back in those days. I am grateful for the time we shared together.

South American Tour

In 2006, I visited four countries in South America on a tour sponsored by the Japan Foundation of Japanese Foreign Ministry. This once-in-a-lifetime experience took me to Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. On this tour I was accompanied by my two best students, Jamie and Minako, and our performance program was a unique mix of Japanese dance and Okinawan court dance.

We had been warned about the tight security measures we could expect before we departed the United States, and we experienced them as soon as we disembarked the airplane in Chile. It took more than an hour for us to get through customs as they carefully checked our luggage. Border security agents opened each bag of costumes and props. I was incredibly nervous, not because we were carrying anything that would land us in trouble, but because each piece had been meticulously packed to avoid damage – many of the stage props were very fragile.

Our first performance was at the University of Chile, and there I was impressed by the staff sent by the Japanese Embassy to help us, as they were so considerate, taking their shoes off to clean the stage just as if we were in Japan. More specifically, the embassy staff, my dancers, and I worked together to do Zokingake (a way of cleaning the floor with a wet cloth while on your knees). Later, we gave a performance at the Ambassador’s residence, which was a perfect setting for Japanese classical dance, including the lovely gold screens.

We did not have the time to do any actual sightseeing, but in between the three performances we gave, we were able to walk around the city of Santiago a little bit. The sky and the mountains were so beautiful and striking, with streets dotted with sculptures. I would love to revisit and see more of the lovely city someday.

After Chile, the next stop on our tour was Argentina. While Brazil has the largest number of Okinawan immigrants in South American, Argentina is home to the second largest Okinawan population on the continent. Although Okinawa lies far across the Pacific Ocean, I learned how strong the Okinawan identity is and how tight the unity of the community is, held together greatly by their traditional arts of music and dance.

In Buenos Aires, we performed at the Okinawa Kenjin-kai Kaikan, or the Okinawan Association Building. The size of the building was impressive: it was three stories tall and included a concert hall, lecture hall, classrooms for Okinawan Karate, and a restaurant. During our stay, we were treated to wonderful food, but the best dish of all – the best Okinawan dish I have had in my life – was at that very restaurant!

I gave my first lecture and demonstration over the course of almost three hours, as the interpreter translated my words from English to Spanish, and then translated back and forth during the Q&A portion. This was a huge challenge as I had had barely any sleep before the presentation due to flight changes and airport delays, but I was very pleased by the eagerness of the audience and the warm welcome they afforded me. The attendance at our performance the next day exceeded expectations, attracting not only Okinawan immigrants and those in second and third Okinawan immigrant generations, but those with other ethnic backgrounds as well. Afterward, we joined the audience at a lovely reception with an array of Okinawan food. I must add that the ladies of the Association were a tremendous help. Even though we did not ask them to, they came to our assistance with hairstyling and costume changes. Without them, the success of our performance would not have been possible.

We finally got to do a little bit of sightseeing in Argentina. A very big treat was to see a performance of tango in San Telmo, the neighborhood where tango was born.

Over the entire tour, we had only one upset. Jamie, one of my dancers, was initially not allowed to cross the border from Argentina into Paraguay, as she was required to present a visa to enter Paraguay. Minako and I were allowed, as holders of Japanese passports, to enter without a visa; Jaime, a holder of an American passport, was not. We had to leave without her while she waited for extra documentation which was quickly arranged by the Japanese consulate. She caught up to us the next day, and it was such a relief! I was glad she was safe and back with our group. The quick thinking on the part of the Japanese consulate had also allowed us to keep to original performance schedule, as she was able to arrive before performances started. I was also very happy to hear that she had spent a wonderful day sightseeing in Buenos Aires.

The TV studio in Asuncion, Paraguay, where I had an interview and showed a short dance, had set up for a coffee commercial shoot. I picked up a cup and posed with a smile; I hope it helped the Café commercial!

Paraguay was a delightful country. While there, we enjoyed meeting with students at the Nihongo Gakko (Japanese Language School). What a surprise it was to see so many youngsters studying Japanese!

Our performances here were held to suit the Paraguayan lifestyle, with the show starting late as 9:00 p.m. We would finish the performance close to 11:00 p.m., and after tidying up, we would get back to the hotel around 1:00 a.m. I found these late nights to be brutal. On our last night, after only one hour of sleep (but really, no sleep) we left for the airport; after the next flight, another long lecture and demonstration was waiting. All I could think of were the words uttered by my neighbor, a French mom: “You do what you got to do!”

The last meal of our tour was at the Ambassador’s residence in Uruguay. The resident cook was Thai and had studied Japanese cooking. The presentation was so beautiful and authentically Japanese – better than we had seen in Japanese restaurants – that Minako, who acted as a photo-recorder of our tour, took many pictures of the dishes. The Ambassador’s wife treated us with a special Japanese sweet, highly prized even in Japan itself: Toraya’s Yokan. For her to share such a rare delicacy with us, sent from halfway across the globe, showed her amazing kindness, and we enjoyed it with profound gratitude. Oh, it was so sweet and delicious!

Congreso Mundial

In 2009, I performed in Spain at an event sponsored by the International Dance Council of Spain/UNESCO, a conference of dance history and dance culture. I performed during an evening program with several other dancers from around the globe. It was wonderful to see dances from other ethnicities while I waited for my turn. It was there that I met the Russian gypsy dancer Julia Kulakova, who would later dance in three of my Salon Series programs as a guest artist. I never imagined such a chance meeting would lead to our delightful collaborations.

During the all-night dance performances, I found myself drawn to Flamenco dance. The most striking dance I saw was performed by a solo Spanish dancer. Her beautiful features were set off by the white pantalone she wore, and rather than the commonly used castanets, she used a cane to create the rhythm of her dance. It had a masculine quality to it, which fascinated me, as it was a stark contrast to Japanese classical dance. Her white shawl against the dark blue of the night sky was so picturesque and is vivid in my memory. To me, the color of the dance evoked by Flamenco is red. But in this case, white, with its neutral quality, evoked a controlled passion rather than the exuberance we usually see. The contrasting expressions of Japanese and Flamenco dance lingered in my mind for the rest of the night, together with that of the beautiful image of the moon against the clear sky.

In all of these places, I was blessed with the opportunity to introduce my art form, sharing its beauty all the while discovering new ways to look at the art through the lenses of different cultures.

At the Airport

While we waited in the Florida airport for our connecting flight to New York after the South American tour, the words Kawara Kojiki (Riverbank Beggar), which I wrote about in Chapter 1, came to my mind. Even though I was called a Kawara Kojiki in a derogatory way, I didn’t mind because it only meant a traveling artist, and I knew the history: It was the term used for the very founder of Kabuki, Okuni, and for the dancers who came after her. Also, the importance of the role of itinerant performers, who placed the cornerstones in the foundation of Japanese performing arts, was inarguable to me. I would be happy to be one of them.

Furthermore, great poets and monks, from Saigyo to Basho, and many more were lifelong travelers. They found not only the truth of life but a home in the natural places they visited on their travels. Traveling was the quest of life.

But it is sad and lonely not to have a home, to be a rootless traveler. The loneliness of the traveler inspired myriad poems and literature, and it seems almost to be a central theme in the Japanese poetry and essays and travelogues.

My friend Jun Maruyama was not a poet, but he sent lines almost like a poem on a postcard from Cape Tappi. He poignantly wrote:

“Cape Tappi is crying with wind,

I cannot keep standing straight.

Despite the harsh, howling wind,

beach flowers bloom here and there,

so naïvely.

The clouds are low, hanging over the Tsugaru Strait.

I am trying to keep collars of my leather jacket high up.”

This coast of Aomori, where you feel like the northernmost edge of the world and the bitter wind blowing on Cape Tappi, has often been used as a metaphor for loneliness.

I have made so many visits to perform at colleges, museums, festivals, and other cultural institutions over my life – almost a hundred in the past 52 years. The most touring I ever did was from the mid-1970s through the 1990s. Then, I used to say to myself, “I spend half of my life in packing and unpacking.” It made me feel as if I was a lifelong traveler, departing from and returning to New York, yet always unsure of whether New York was a permanent or temporary abode of mine.

After all, we are all travelers forever seeking home, peace, stability, and comfort. It seems to me that the cosmos provides us with everything we seek, just as it did for our predecessors, even if in unexpected ways. Our own individual universes surround us with the things that make our homes: dancing, teachers, students, audiences, people’s smiles, sunshine, flowers. I am blessed that my little universe has been able to expand through the encounters I have had in my travels through America, Europe, South America, Greece, China, Singapore, and so many other places.

Dance has been the language I have used to make so many new friends; Russian dancers, Flamenco dancers, the orphaned children with whom I danced in Kathmandu. Dancers who have taught me, and those I have taught. I am a part of them, and they are a part of me.

I can still picture the scene at the airport after the South American tour: We three dancers, while waiting for the plane to New York, sitting on the floor with our luggage around us, tired by the whirlwind of touring four countries. Quiet but content, looking at the empty space: We were happy Kawara Kojiki.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: CHAPTER 8

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

Summer Festivals and My Roots

August is the time of O-bon holidays, when the Japanese honor their ancestors and welcome their spirits home to visit. My childhood memories of this time are of visiting the cemetery with lanterns, and being scared by fireworks under my geta clog, thrown by neighborhood boys. We children half believed we could talk to our deceased grandma or granddad. These were sweet and innocent times, and each year, the summer breeze brings them to mind.

O-bon developed as Japanese traditional beliefs and Buddhist customs of honoring ancestors merged. A holiday known for its large bonfires, O-bon coincides with Natsu Matsuri, or local summer festivals. These festivities of music and dance meant to welcome the spirits of the ancestors are a time of vigor and energy, which seems contradictory to traditional Japanese culture’s emphasis on reserved manners and maintaining grace and subtlety. Sometimes they can get quite rowdy; in the town of Nishimonai, which I visited in 1974, I heard there had been drunken clashes between the carriers of the mikoshi, a portable shrine, and the villagers, resulting in at least one death. Perhaps, being subdued for most of the year, people need time to unleash their pent-up energy. Even into the 1960s and ‘70s, countryside areas focused on farming and fishing maintained very traditional lifestyles, where liberties could not often be taken. Festivals in Tokyo, where one could find more freedom of expression in daily life, seemed to tend to be calmer.

Minzoku Geinoh (Performance Folk Art)

Learning about, or rather, peeking through the door into a new world of dance, culture, and art in New York from 1972 to 1974 made me think closely about the roots of my own dance form. Back then, I only knew about the precedent to Kabuki, which is the Noh Theater, and had very limited knowledge on anything earlier. I realized that I was insufficiently equipped with the resources and knowledge I would need to continue my mission of introducing Japanese dance to wider audiences, and I felt an urgency to know where my own tradition came from. Upon finishing my MA in Dance at NYU in 1974, I returned to Tokyo from New York, and embarked on a journey to investigate the roots of Japanese classical dance so that I could discuss my dance tradition with American audiences and students in more depth.

In my quest for knowledge, I turned first to Minzoku Geinoh, the performance folk art, from which Kabuki — and eventually Nihon Buyo, the classical dance – developed. This led me to my next focus: Okinawan dance and culture, which has preserved early Japanese traditions while maintaining its unique cultural identity. My investigations into Okinawan dance led to my doctoral research in the 1980s.

Minzoku Geinoh has led to many traditions that are still alive and vibrant around Japan. I could not have discovered everything I did without the help of many people. Reflecting on it now, there were so many people I interviewed who did not mind sparing their time, giving me guidance, and teaching me the richness of the Japanese heritage.

My first guide through performing arts festivals — in the 1970s, there were many as 10,000 around the country — was Dr. Haruo Misumi. He is a well-known scholar on folk ethnology and a proficient prolific writer of many books on the performing arts. He recommended several festivals to me where I could witness the most beautiful and significant dances in searching for the roots of Japanese dance.

One of them was Nekko no Bangaku in Akita Prefecture. I had an interview with older performers and musicians, and it saddened me when they expressed their concern that there would be no more people who could transmit the traditions of their music after they died. Although the young people from the village were required to perform Bangaku at the local festival, none of them had learned the old music. It was not yet the millennium, but the 1970s, and the disruption of the transmission of old folk traditions from one generation to the next was already happening around the country. Now, with renewed recognition of traditions, I hope younger generations have regained the energy for performing, despite the difficulty of passing down an oral tradition.

In another distant area, Shiraishi‐jima Island in the Seto Inland Sea, the villagers welcome and send off their ancestral spirits (at) with their version of Bon Odori, Shiraishi Odori, during the summertime. My guide that night was an old lady. That evening was so beautiful; we were on the beach, and danced there in the moonlight. From time to time, she would sit on a straw mat to rest, while I listened to her delightful stories of her dancing in the festivals in the past.

Shiraishi Odori, Kasaoka, Okayama

I also made a visit to Gujo City in Gifu Prefecture to see their summer celebration. Gujo Odori is known for having a wide variety of Bon Odori dances and songs. Walking around, I was surprised to see many shops selling geta, or traditional wooden sandals, in the city. Why? Supposedly, after dancing all night, the dancers would have worn their geta out! One woman I interviewed told me her memory of dancing all night long. When she was tired, she would sit and rest for a few minutes, and then get back on her feet to dance until dawn. Dancing all night long used to be common in many Bon Odori, but has been banned for the past few decades due to security concerns voiced by village and town councils.

During these years I met one of the pioneering scholars of ethnology, Dr. Yasuji Honda, who was collecting data and conducting interviews of his own. It was an honor for me to meet him: he was so kind as to give me some professional direction, along with his thoughts on festival culture and suggestions of some festivals that I should observe. He must have been in his 80s, but he was still on his own two feet doing fieldwork. Witnessing this, my bow to him was very deep, with respect to his lifelong work.