SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: Chapter 7

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

Dojoji: Dojoji 2001 and 2002

July finds us halfway through the year, as far from its beginning as its end. In traditional Japan, this is a time to perform Misogi – a purification ceremony meant to cleanse and renew the spirit after half the year has passed. In modern times, we try to relax and enjoy summer’s slower pace, storing our energy for the busy autumn that awaits us; even Christmas feels like it is “just around the corner.”

Thinking ahead to the holiday season reminds me of the New Year’s Eve ceremony called Joya no Kane (Bell on New Year’s Eve), an important occasion for the Japanese to close out the year. During this event, a temple bell is struck 108 times. These 108 tolls represent delusions we have had during the course of the year, one driven out with every strike. Listening, we are slowly cleansed, and we can welcome the New Year with a fresh mind, soul, and body – a great panacea. The sound of the bell being struck and the resonance of sound after the strike helps us to meditate on the past year as it passes away from us.

Along with the bells of the New Year, there is another bell that has rung throughout my life: that of Dojoji. You may remember the story of Dojoji from the previous chapter – a tale of transformation, revolving around a woman’s unrequited love and its disastrous consequences. The characters in the dance are a maiden and a monk, but it is arguable that the bell, although inanimate, is a character in and of itself, and a very important one.

Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji — Pointing to the Bell

“Sachiyo Ito is a graceful dancer/choreographer/teacher of quiet power. On April 2, 200I, she offered Dojoji 2001: an 'Evening of Japanese Classical and Contemporary Dance’ . . . they crafted a subdued tension around the topic of unrequited love, in a modern interpretation of ‘the timeless drama of human desire and transformation.’"

— Madeleine L. Dale, Attitude 2001

The Challenge

The Dojoji legend is one of the oldest and best known in Japanese folklore. Dating back to the eleventh century, it was turned into a Noh play in the fifteenth century and then into a kabuki play in the eighteenth. It is such a popular theme that it effectively became its own genre, called Dojoji-mono. This legend has become one of the foundational works of Japanese performing arts.

Creating a new work in the Dojoji canon can be considered a kind of revolt against tradition. It was a challenge to create my own dances for Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji (Maiden at the Dojoji Temple), the well-known Kabuki dance drama that was first staged in 1753. Among many Dojoji dance dramas, Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji depicts the sequel of the Dojoji legend and is arguably the most enduring Kabuki dance. Incredible costume changes, breathtaking colors, and the dramatic change of the heroine from a beauty to a monster against the background of spectacular cherry blossoms have ensured its popularity over the centuries.

As a classical dancer, to perform Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji is considered reaching a pinnacle of one’s art, for it shows absolute mastery of dance and acting technique. One needs the permission of one’s dance school to perform it on stage. During my early years in the U.S., my aim was to introduce the most emblematic dances of Kabuki to American audiences; therefore, I presented Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji at several concerts: the American Dance Festival (my debut in the U.S.), Riverside Church Dance Festival, and at events at Japan Society and Lincoln Center. I danced it just as I was taught to, every time, for many years.

Why then, after so long, did I take on the challenge of creating my own Dojoji dance? The answer is simple: I wanted to cut through to the heart of the dance itself. The heroine has real emotions that are hinted at in a very subtle manner throughout the dance. However, the storyline gets lost in the accompanying lyrics, and it ends with an abrupt and surprising change of character. Coupled with the intense visuals on the stage – the many outfit changes, the falling cherry blossoms – the dance seemed to me to be too ostentatious, becoming nothing more than a costume display.

Looking back now, I realize that some of my motivation lay in having seen many innovative works outside of Japan, particularly in New York. After almost thirty years of performing in the United States, I felt that it was time to create my own works. Perhaps I was too bold. But in those days, at the turn of the millennium, I felt a different awareness around me, and hope for the new era. I wanted to see Dojoji with fresh eyes, in the context of the new epoch we were entering, rather than the usual story of love and hate. I wanted to focus on the universal theme of the human condition, a theme that transcends time and space, east and west.

During the 1990s, I was fortunate and blessed to encounter the teachings of Tich Nhat Hanh, and I created dances inspired by his poems. Then, as I began to perceive the Dojoji story as a new work, I could see my vision and choreography clearly through the lens of his teachings. I am more grateful to him than any words can express for the inspiration he gave me for both Dojoji and my life’s work.

In creating the new version, my goal was to expand on the themes of desire and destruction, but in a global context: Obsessive desire for modern technology and material things leads to the destruction of environment and ecology; racism and tyranny result in wars among nations and devastation of culture.

The first version of my entry into the Dojoji canon, Dojoji 2001, was presented at the Sylvia Fuhrman Performing Arts Center in 2001. The second, Dojoji 2002, was presented at the Theater of the Riverside Church at the 30th Anniversary Concert commemorating my U.S. debut. There was development from 2001 to 2002 in the scale of the production: Dojoji 2002 had a longer performance time and more actors and dances, along with an expansion of music, poetry, and sets.

I am aware that I went far beyond my capacity for artistic expression and technique and resources available for the production. However, in the undertaking, I realized we could apply the global themes of Dojoji 2001 / 2002 on a personal level, to our day-to-day lives.

We can see our emotional turmoil resulting in tired faces, mirrored in our own bathrooms. How can we come to terms with ourselves? Is there any way to find peace within our own hearts? Perhaps, if we can find peace within us, then peace on a larger scale is possible.

These questions and thoughts led me to create a new opening scene, a walking meditation, each step carrying the minds of both the performers and audience closer to the heart of these matters. If my efforts to pose these questions and show these trials touched only one person, then the overexertion will have been worth it.

The Genre and the Bell

In the Dojoji story, the focus of the narrative is on love and hate between a woman and a man. A woman, Kiyohime, falls in love with a monk, Anchin, who spurns her advances. Rejected, she turns herself to a demonic serpent who chases the monk. When the monk takes refuge in the Dojoji Temple, the woman destroys both him and the temple bell, inside which he is hidden, by burning them to ashes.

The genre Dojoji-mono is divided into two groups: one that follows the original storyline; the other, a sequel that takes place a few hundred years later. There is a myriad of versions of the tale in the first group. According to the Engi Emaki (Scroll of Origin of the Temple) handed down at the Dojoji temple, the sequel took place 400 years after the initial incident. Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji belongs to the latter genre.

In the sequel, the monks are raising a new bell to replace the old one. Women have been barred from the temple, but a maiden enters regardless, and begins to dance before the new bell. At the end of her dance, she reveals herself as the demonic serpent, just as from the original story, and leaps into the bell.

The bell is of grave importance. For not only does it serve as a symbol of the woman’s desire, longing, passion, anger, jealousy, and eventual self-destruction, but it is also a symbol of taboo, human delusions, and attachment. It also functions as a symbol of Buddhism. The importance of the temple bell in both Buddhist teaching and Japanese culture is illustrated by the opening lines of the medieval story The Tale of the Heike Clan. The concept of impermanence is depicted most beautifully through the sound of the bell as its ringing fades away.

The sound of the bell of the Jetavana Grove echoes the impermanence of all beings.

The color of flowers of the shala trees teaches us that the prosperous ones must decline. The proud noble ones can live no longer than a spring night’s dream does.

The strong warriors shall perish at the last.

They are nothing but dust before the wind.

There is another play in which the bell takes center stage. In Miidera, named after the temple in which the play takes place (known as having one of the three best sounding temple bells in Japan), we find the same setup as Dojoji: The temple is off limits to women, and they are forbidden to enter. In Miidera, the woman has entered the temple to search for her lost son. In both stories, women enter the temple despite the prohibition, breaking a taboo in the process. However, in Miidera, the woman strikes the temple bell and is reunited with her lost child, evoking a sense of selfless love. Here, the bell brings two people together and remains whole. Conversely, in Dojoji, the woman enters the bell, as if to be united with the man inside, and emerges as a snake, capable only of destruction. The bell illustrates transformation, but ruinously so, and lies broken in the end.

To elaborate on references and implications of myths of the snake throughout the world would take more pages than I am allowed here. However, in Japan, the snake has been seen as a metaphor for the hideousness within, and to me, it is an expression for both the hideousness and ugliness found in the mirrored image of ourselves, caused by the negative seeds we carry within, such as attachment and anger.

I used to use the word for the story of Dojoji as “surrounding” the bell and the woman. The coiling, spiral movement and image around the bell illustrated the transformation in us humans and non-humans perfectly.

The Research

Prior to the creation of my work Dojoji 2001, I researched its background heavily. This included visits to many folk performances of Kagura such as Kurokawa Noh in the northern Yamagata Prefecture, where Dojoji is titled as Kanemaki; Kumi Odori (Okinawan Court Opera), titled as Shushin Kaniri in the south; and several performing arts in surrounding areas, including Mibu Kyogen in Kyoto. Of course, I also made the essential pilgrimage to the Dojoji Temple in Wakayama Prefecture!

Watching the Kurokawa Noh performance was a big assurance about the centrality of the bell in the story, as it is the essence that threads throughout the storyline. To me, the bell became the main character of the story. The other, presumed protagonist was not there; I said to myself, “Where is the handsome man?” The absence of the man becomes a source for our imagination and fantasy. An appearance of the man would destroy the fascination, although he has been depicted in plays and dances. To me, the imagination inspired by the story and symbolism of the bell seemed to be compelling enough on its own.

Upon visiting the Dojoji Temple, I was surprised to see countless donated plaques and photos, displayed in the alcove of the main room of the temple, with words of prayers and gratitude. These had been offered by actors and actresses in kabuki, modern theater, and film who had visited the temple to pray for the success of their performances.

Another surprise was the number of tourists from around the country, as many as a hundred visitors a day – the count at the time when I visited the temple. I gave a sigh; the Japanese, young and old, through the ages and even now, have been fascinated by the Dojoji story. I took the hour-long group tour led by the Abbott, and we all listened intently to his convincing, vivid storytelling as he showed us the Engi Emaki scroll.

Since the Dojoji legend was born as a Buddhist morality tale, the scroll ends with paintings describing both Anchin and Kiyohime becoming Bodhisattvas, after being saved by the prayers of the Abbott, and entering enlightenment and reaching the Pure Land of Western Paradise. Another surprise! Such salvation does not happen in Noh and Kabuki, which I’m sure you can well imagine.

Then, I visited Hidaka River, for I was curious as to how dangerous it was to cross it. The Hidaka-gawa Iiriai-zakura (The Hidaka River at Twilight Cherry Blossoms) of Bunraku Gidayu (the puppet drama) describes the scene of Kiyohime’s transformation upon having to cross the wild and rushing river. The drama depicts the argument between Kiyohime and the boatman, who rejects her request to take her across the river in his boat despite her pleas, and this prompts her transformation. Turning herself to a serpent, Kiyohime swims through the river, as long as 192 kilometers (119 miles)! But even before arriving on the bank, she had already run the distance from the Masago village, where she began her search. The road of the hunt for Anchin to Dojoji along the shore is now called Kiyohime Kaido (Kiyohime Shore), which is 960 kilometers (596 miles). After the river, it is another 15 kilometers (9 miles) to reach Dojoji Temple. The length of the New York and Tokyo Marathons are only 42 kilometers (26 miles), so she is the world marathon record holder. What a power her passion and desire propelled!

Upon arriving at the river, I was disappointed to find only a dry riverbed. Well, indeed, I thought to myself, it was a long time ago.

As for the cursed bell, ever since it was burned down, reinstallation has never been successful. Every time a new bell has been installed, it is said to have brought disaster, such as famine and natural calamities. Still, the site on which the bell stood has been enshrined. Though there was no bell, it has attracted visitors for many centuries – a good lesson in encouraging tourism.

Inspired by the comical direction of the Mibu Kyogen performance I saw at the Injoji Temple, I have incorporated comic elements in my choreographies of Dojoji, including dialogues between the monks and visits of modern tourists to the bell site. A humorous touch was often used to preach Buddhism to commoners in medieval Japan; those touches of levity also play a role in highlighting the impermanence we experience in our lives.

One of the caretakers of pilgrims and visitors to the temple was a lady in her 80s. She was incredibly kind to me on my first visit in 1999, and I did not forget her. In 2003, I surprised her by returning to the temple, showing photographs from the performance of Dojoji 2002, which she was very excited to see.

“The Bell at the beginning of the night

echoes forth impermanence of life

The bell in the middle of the night

Echoes forth all that are born must die.The bell at the dawn resounds with destruction of all,

While the bell at dusk resounds with infinite joy

that invites those who leave the mortal pleasures

to Nirvana.”— From Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji

In these lyrics, as well as similar lyrics in the Dojoji in Noh, the bell and its toll symbolize Buddhist teachings of impermanence, as mentioned earlier. Further, the bell has another representation as well: that of salvation. The physical construction of temple bells was costly, and a donation to the temple for this purpose was seen as an act of repentance. Pious donations could pave one’s path to Nirvana. There are centuries of lists of donations of precious combs and hair ornaments from women who wish to be saved; this record becomes all the more poignant when held up against the Dojoji legend.

There is a phrase in the lyrics of Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji that keeps running through my mind. “The clouds of the Five Hindrances are cleared now, so now I can watch the moon that shines the truth.” That means we women supposedly have five hindrances for reaching enlightenment, since we have delusions and desires, and are not pure.

In my youth, I used to think, “So men are pure, clean, and have no delusions?!” In both Miidera and Dojoji, women were able to break the taboo and enter the temple, but the problem was that there was a taboo to be broken to begin with. My naïve impression was that most temples (depending on the sect) were very discriminatory. I took this question to my teacher. Perhaps she thought I was too young to understand the meaning of the words, as she only suggested that I go up a mountain to watch the clouds clear from the sky. I did go up somewhere to watch the sky. This did help in executing one movement with a fan, for it became deeper once I had a better picture of the landscape in my mind, but I did not achieve any clarity on the Five Hindrances! It was only much later, when I found the concept expanded on in an encyclopedia, that it became clear. The ultimate teaching is, of course, that both men and women can enter Buddhahood through Buddhist Practice.

The Fantasy

Surrounded by the full-blown cherry blossoms, beneath their gently falling petals, a beautiful dancer performs and charms the temple monks. Suddenly, she transforms into a demon. In Noh, the mask used for this role is called Hannya, a demonic mask used to portray women in the throes of jealousy. There is a distinct lack of demonic jealousy masks for men. Why have there been no such demons in classical plays? Well, men wrote the plays. They wanted to be loved and chased as much as they wanted to die heroic deaths. Or perhaps, was it a playwright’s act of revenge to write about jealous women, a reflection of his own unrequited love? Was it simpler – just an awe of one sex towards the other?

The Collaborators

Robert Mitchell, who created many sets for Broadway and off-Broadway shows, was so gracious to collaborate with me again after my productions of Poetry in Motion at Lincoln Center’s Clark Studio Theater and Joyce SoHo in 1990 and 2010. It was he who created the bells for my production of Dojoji. Without the bells he created, my Dojoji would not have had the impact it did. They served successfully as a symbol for the timelessness of the themes of the story.

One bell was a replica of the Noh theater style made in damask, while the other was his own interpretive creation. His second bell was ingenious, transforming mid-performance. It began as a ring on the floor, which rose toward the ceiling at the sound of the first bell. Thus, the shape of the bell materialized, telling us that a centuries-old story has awakened and now repeats, hinting the universality of the themes. I had a novice striking the classical bell, as the act of awakening the spirit of Dojoji. My hope was that the toll of the bell would evoke the timelessness of an endlessly cycling story. The striking of the bell would also awaken the ghost of Kiyohime from her long sleep, then drive her to the bell, the symbol of her desire and anger.

I must commend Bob’s amazing professionalism and willingness to go above and beyond in his work. For example, to make a special sacred area on the stage, he suggested that we go to a carpet store and look for a carpet that could allow me to dance with a gliding walk – to me, this seemed like an impossible idea. We looked at so many materials at the carpet store and eventually found one! He was also known for his accuracy of measurement in creating exact diagrams for building stage sets, which once led him into a heated argument with the theater staff about its measurements and specs in one of the theaters where we had productions. I still recall the unforgettable, innovative, and beautiful sets he made to depict underwater and sacred shrine space scenes at the French Alliance Theater for the 25th Anniversary of my debut in the U.S. in 1997.

In 2006 I visited Bob at his home. He was bed-ridden, but he and I were able to exchange smiles. The following day, he passed away.

For many years afterward I used to think about the bell he made. One day I visited his friend Patrick in their loft. It was a brief visit; he came to the door in a wheelchair that had to be lifted up the stairs by his aide. I was grateful, even though we only had a chance to exchange a few words. His eyes were as gentle as Bob’s.

I was also fortunate enough to work with creators such as the mask maker Sarah Bears and the costume designer Reiko Kawashima. I still have the stuffed snake Reiko made. How she carried the heavy and enormous snake to the Riverside Theater, I still do not know. We worked together often, and she became my favorite designer for other dances.

For Dojoji, I got to work with young male dancers who were either hip-hop dancers or trained in classical ballet, and it was a very interesting experience for me. In addition to Dojoji, I trained them in an Okinawan dance piece, accompanied by drumming, happy tunes, and fun-filled movements, to contrast with Dojoji’s heavier story. Meanwhile, for Dojoji, I fused Okinawan movements and elements from the Minzoku Geinoh with the classical male style dance as its choreography. I was very pleased that they could incorporate these mixed styles.

I do not list Mr. Shoji Yamashiro (AKA Ohashi Tsutomu) as a collaborator, but as an artist who contributed to creating Dojoji 2002. Like fate, I came across his music, Gaia Echophony. I asked for his permission to use a part of the work, and he was so kind as to encourage me to use it. I incorporated it with live music and other newly recorded sounds.

That word – Gaia – pursued me then. It was such an intriguing word. Twenty-five years ago, we were not as aware of the words “climate change” as we are today, words which now alarm us, as we realize the threat to current and future generations on earth. I discovered the Gaia Hypothesis, an idea that took hold of me and never let go. Gaia comes from Greek mythology; she was the goddess that personified the Earth. The Gaia Hypothesis is the idea that Earth and all of its biological and ecological systems form one single entity. Whether you believe it or not, understand it or not, one must at least acknowledge how deeply we are interconnected with the world around us. Humans and other beings, both sentient and non, cannot exist without others. Chains of events affect everything on the earth, both in positive and negative ways, and climate change has now become the most pressing matter. The very interconnectedness that defines us has the power to destroy us. If the changing world is the strike on the bell, are we doomed to fade away in its echo?

Looking back at my work now, I can say that I was headed in the direction to explore these concepts, but I did not sufficiently coax them to the surface. Then, I was unable to do so within my capacity; that exploration was beyond my comprehension and vision. Now, at this age, and as I write my memoirs, I have begun to seek a way to express it, even if only in a minor way, with my next project.

Gaia, nature, and the dance…

My Mother’s Funeral

My mother was ill for 8 years.

I was her only daughter, so my brothers looked to me as the one to be by her side. At the beginning of her illness, I took care of her in New York for ten months, after which she received care at a hospital in Massachusetts. After that, though, she had to go back home to Tokyo, where she felt the most comfortable.

During the years that followed, I would fly to Japan to be with her whenever her illness became serious. I flew back and forth between Tokyo and New York more than twenty times in seven years. The last time I flew to Tokyo for her was for her funeral, and I arrived from the airport in the midst of her wake.

Next day, I placed the postcard for the Dojoji production in my mother’s coffin, beside the white silk of her kimono. “I’m very sorry, Mother. Please forgive me, though I cannot stay and accompany you to the crematory. I hope you understand. Please watch the dance from up above.” We were in tears as we surrounded her to say goodbye. I had to leave then, to catch my plane to New York. Dojoji 2001 would be performed in less than a week.

Cancelling my productions or any performance engagements because of personal or family matters has not been an option in my life. For that matter, even when I broke my foot, I performed several times.

That moment as I stood by the coffin, there was nothing in my head. It seemed that time froze as if we were in eternity.

Empty Bell

Press against our hearts

Bell of empty resounding.

Your dying note, an

Amulet across eons:

The medallion of desire…

Beauty of Gesture

Is captured after it

Has been lost: voidness

Embraces us, puppets of

Play in a cave of shadows.Since nothing endures, nothing is destroyed; since

Nothing is, nothing

Is not, since there is nothing

To know, knowing is nothing.

— Mackenzie Pierson 2001

The bell and the man were burnt to ashes, and we all return to the earth.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: Chapter 6

Photo by Heather Shroeder

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

TRANSFORMATION

Ichikawa Shojo Kabuki (Ichikawa Girls’ Kabuki)

Greetings to June!

Welcome to the season of utmost beauty, heralded by shimmering light emanating through bright green leaves.

The Japanese have a word dedicated to this: komorebi, which means “sunlight leaking through leaves.” The transformation of glorious light to beautiful shadows dancing on the forest floor reminds me that transformation has been a central theme that runs not only through my work, but my life.

My training in professional performance (stage debut was in 1956) began in the late 1960s, when I joined the Ichikawa Joyu-za (Ichikawa Actresses Troupe) as a member of the chorus. The troupe was originally called Ichikawa Shojo Kabuki (Ichikawa Girls’ Kabuki).

Kabuki is known worldwide as an all-male theatrical discipline. However, in 1948, this all-female kabuki company was founded.

Ichikawa Shojo Kabuki was a sensational success during the early Showa Era (1926–1989) because the girls were phenomenally good actresses, playing both the male and female roles of the standard Kabuki plays. The company did not tour the mainstream stages, but rather local towns and city centers in various prefectures. Their acting, singing, and music in Gidayu was so good that the audience (including myself!) would often be driven to tears during the performance. As the years passed and the members of the troupe grew older, the name was changed to Ichikawa Joyu-za. The entire company—from the actresses, musicians, and singers to the stage crews and costume hands—were all female, with the exception of the choreographer. My impression of him was that he was very strict, as befitted one in our tradition. I was honored to join and gain valuable stage experience and learn the makeup and costuming.

Since the troupe gave performances at locations off the beaten path, the facilities were not as nice as they were in the big theaters. The backstage areas and dressing rooms in these old buildings could be quite drafty, which was difficult in the winter. I remember how cold it was to paint oshiroi, the white kabuki makeup, on my face and neck with a brush dipped in icy water. Touring with actresses whose whole lives, from childhood onward, twenty-four hours a day, were dedicated to performing, was a wildly different experience from what I had grown up with in the traditional Japanese dance circle. It taught me about what professionalism as an artist is.

Did their artistry of acting, of transforming into the characters’ personification of men, mean they were attempting to capture the other gender’s quality? I wondered if it is a human desire to act as the opposite sex. Eventually I realized that it was a different philosophy: They did not want to become the opposite sex, but to accomplish the transformation of their art and become whatever the character needed to be—male, female, somewhere in between, or without gender of any sort. I believe it was the human emotions, the suffering and love, that they did best to express through characterization. The universality, when and where (centuries ago/Japan), did not matter.

They were keen to listen to the choreographer’s critiques after each show and to dedicate themselves to improving for the next one. For them, acting was not just a desire for transformation, but their life, their breath, and their blood.

AIDS Fundraiser Performance

In the early 1980s, New York was poised on the eve of a great cultural shift, although I didn’t realize it at the time.

A career in the arts generally placed one in queer or queer-adjacent spaces, although the culture seemed to me to be more discreet than it is now. There was an exclusive club on East 51st Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues called Garden Club, or GH Club for short. The front door used to reveal a crowd of men in formal attire, dressed extremely well in suits and ties. A sense of pride prevailed in the club, and one sensed it was a privilege to be there. This was one of New York’s gay clubs. Although I was not one of them, I was allowed entry since I was a friend of the owner, Giro, my former dance student. The atmosphere was protected, safe, and the guests’ manners were graceful, gentle, and never vulgar.

Giro drank vodka; according to him he liked it as it does not smell of alcohol, which might be unpleasant to his patrons. That was one of his criteria of being a true “gentleman.” His mottos were “Be dressed well so that your partner, guests, or friends won’t be embarrassed at a gathering,” and “Be punctual; keep your appointments.” He hated those who broke them. I know when his finances dwindled down and he had no decent suits to wear, he borrowed formal attire like tuxedos from friends when the occasion called for it.

One day in 1983, Giro asked me to perform for an event at his club.

“Do you know AIDS? We are doing a fundraiser for it.” This was the first time I had ever heard of AIDS. It had only appeared in America in 1981 and wasn’t even called AIDS until late 1982. Even for some time afterwards, many of those around me had never heard of it, and widespread awareness would not happen for several years. So, the fundraiser held by Giro in 1983 was one of the first of its kind.

The event took place over several days. There was an artwork auction featuring works by Warhol, Vasarely, and Mapplethorpe, opened with a champagne reception. The main event was a brunch, which is when I performed. The event was a runaway success, and the club was so crowded that I had nowhere to dance except on top of the grand piano! I do not recall how much money Giro raised, but he was very pleased with the good result.

Giro was my friend for a decade, but we only used to meet a couple of times a year. Sometimes we would meet for tea at the Plaza Hotel—he took all of the nuts on our table upon leaving as a souvenir (!) although you can imagine how embarrassing it was to me, to behave thus while being surrounded by beautiful people. Another time we went for a drink at One if by Land, Two if by Sea, one of New York’s most storied restaurants. He would tell me that his boyfriend was a member of the Italian Mafia, and I would think it was a joke, but it might have been true. On one occasion, he entrusted me with several paintings, which I kept at my apartment. Several months later, I was asked to return them. That night, returning the artwork in a torrential rainstorm, was my last visit to the GH Club. The evening affair reminded me of a Jiuta-mai dance, in which there is a gesture of the heroine looking at her sleeve. This translates for a woman looking at the teardrops gathering on her sleeve, expressing sadness. I looked down and saw that my kimono and I were indeed wet. Afterward, I discarded the drenched kimono I was wearing, recognizing it as a kind of metaphor.

Many years later I bumped into him on the street right in Chelsea, where I had just moved. He told me he was staying with a friend whose entrance of the apartment building had a lovely spiral staircase, just around the corner. He invited my mother, who was visiting me then, and me to dinner, and I accepted his invitation. But remembering his drinking, which my mother noticed at one brief meeting we had had before, she declined the invitation. I believe he must have come to my building exactly at the appointed time. I haven’t seen him since.

Whenever I pass by an apartment with a spiral entrance on 23rd Street, although I am uncertain if that was where he stayed, I imagine he might appear, well-dressed as he used to be. Is he alive, well and happy? Or has he passed away?

Just a year ago, I noticed a Pride Flag held by the window of the apartment.

I only pray wherever he is, on earth or in heaven, that he is happy and enjoying his vodka.

Chieko and Dan

I have a dance titled under various names: Chieko, Chieko-sho (Chieko Anthology), Chieko Genso (Chieko the Element). The name has been changed with each new revision and presentation. Without the first presentation with Dan Erkkila, the composer, and the singers and actresses at Japan House in 1974, I would not have repeated and revised it so many times. This makes it sound like I was unhappy with Dan’s work, but it was quite the opposite: The music is so lovely that I keep coming up with new ideas and choreography for it.

Dan was a composer and flute player, who was introduced to me by Jean Erdman, the modern dance pioneer, who was a board member and supporter of my company for many years, and Teiji Ito, a great percussionist and improv musician. Teiji was the nephew of Michio Ito, another legendary modern dancer. Their great teamwork, often including Teiji’s wife, Cheryl, was an inspiration for me to produce works in my early days. We had fun performing together as an ensemble in such places as the Theater of the Open Eye, the YMCA at 53rd Street, and New York Botanical Garden. The last time I saw him was at Bellevue Hospital, where he was getting treatment for AIDS. Unfortunately, he succumbed to it in 1992. He was far too young to leave us without more of his beautiful music, one of the many bright talents whose lives were taken by this cruel disease.

I remember the time when he and his friend Steven allowed me to stay at their apartment on Bleecker Street while I was looking for my own place. On the walk downstairs from their fifth-floor apartment, the fragrance of baking bread from the Italian bakery on the first floor would reach me, and it was so inviting! The bakery was one of the oldest establishments in New York City. I never tasted it, since by the time I came home and was ready to buy bread for supper, the day’s bread was sold out – rumor had it, by noon! The 1970s and ‘80s were the good old days in the Village. It was a home to many artists, with Italian cafes with Italian paintings and old rugged couches, rusty gold-gilded espresso machines, and the most delightful espresso.

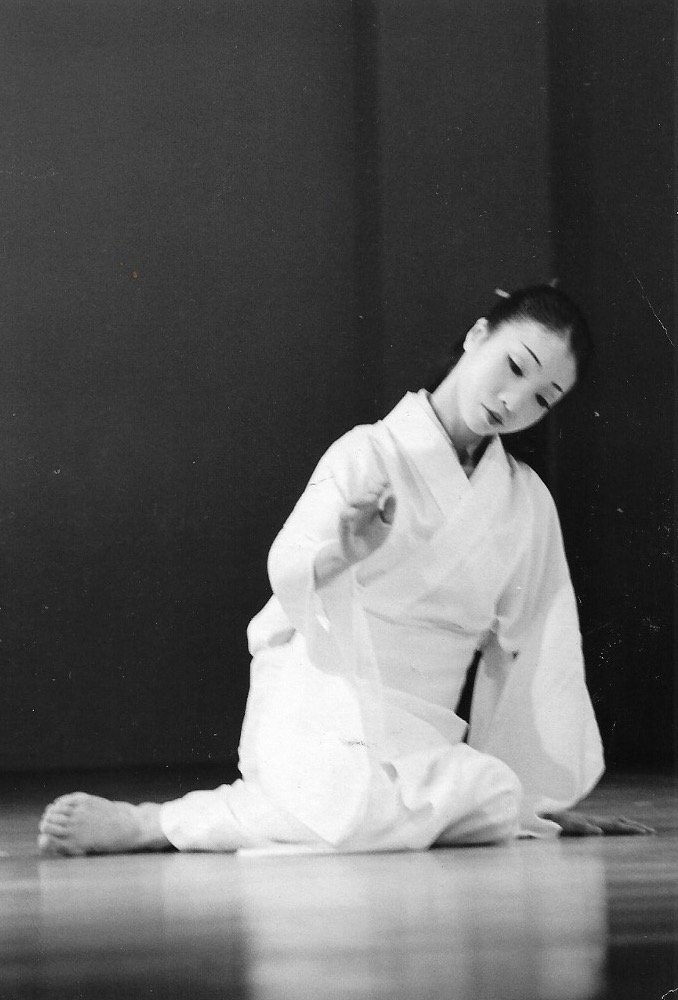

In Chieko, Dan’s ephemeral music intoned by the female chorus made it possible for me to leap into the world of Chieko. It was a place where you could play, a world beyond humanity, a world of insanity, a world of transparency. For this dance, I chose a white costume, a symbol of death, because it seemed there should be no reality, no color, no happiness or unhappiness. We did not have any set, no backdrop, just a simple spotlight in a few sections. I loved the spare space, the vacancy. While dancing, there was someone in white in the darkness.

Chieko. Photo by Ray Smith

It was only decades later that I was able to explore more of the world of “fantasy.” That was through the collaboration with Robert Lara at my series of performances called “Salon Series.” He introduced us to the world of Mexican mythology, bringing the world of a thousand years ago to life.

Fantasy and Illusion of Transformation in Theater and Dance

I was very fortunate to have Mr. Robert Lara accept the invitation to appear in my Salon Series No. 59, titled “Fantasy and Illusion of Transformation in Japanese Dance and Ballet,” in 2017. Mr. Lara, who heads the New York Baroque Company, was a soloist for the acclaimed Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo. Very graciously he offered to give a presentation of makeup used for him to become a queen of Mexican legend, and we all watched as his makeup artist demonstrated the application of makeup on him. He also discussed the transformation of genders in ballet and performed an excerpt from his work La Catrina. (La Catrina is a symbol for the Day of the Dead, Mexico's lady of death. She reminds us to enjoy life and embrace mortality.)

The large number of attendees we had showed keen interest in the subject of transformation. Perhaps in our daily lives we have an unnoticed desire in our subconsciousness to experience transformation for ourselves, as shown in the symbolism of Mexican mythology, which went beyond mere reversal of gender roles.

We had planned to give the second collaboration in June 2020 with a different theme, but unfortunately, it had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

My next exploration of transformation was with Ernest Abuba at Salon Series No. 69. Ernest was an actor, director, writer, and scholar with whom I had the honor of collaborating in several Off-Broadway productions, including Shogun Macbeth.

Transformation and Transition: Kabuki, Shakespeare, and Now

For a Japanese dancer, it is a joy to become the character of a Kabuki dance: the wisteria spirit in Wisteria Maiden, for instance, or the heron in Heron Maiden, tormented by unrequited love. I love dancing these roles.

Fuji Ondo (Wisteria Melody) from Fuji Musume (Wisteria Maiden)

Sagi Musume (Heron Maiden)

However, playing the role of a man is the one I find so interesting and fascinating, as well as a challenge. I particularly love Wankyu, the character from Sono Omokage Ninin Wankyu (Wankyu, the Two Shadows), a Kabuki dance first staged in 1774. In this story, the man who cannot live without the woman he loves goes mad. The music is superb and lyrical, and at one point it seems to be too fast a tempo to dance!

Up until 2021, I had only had the opportunity to perform this role once, at my recital at Japan House, inviting Sahomi Tachibana to dance with me in the role of Wankyu’s love, Matsuyama. Nonetheless, I used to practice the dance all the time, almost as a compulsion. In the summer of 2021, I was lucky enough to have a good young dancer as an intern and train her in the role of Matsuyama. The dance was presented at Salon Series No. 69.

Wankyu (Wanya Kyubei) in Salon Series No. 69. Photo by Heather Shroeder

During this presentation, we looked at transformation from various angles: from one gender to another, from the ordinary to the extraordinary. We also considered the transformation of actors and dancers in characterization through different times and places: from Shakespeare to Kabuki and from the sixteenth century to the present.

It was wonderful to dance Wankyu, but discussing transformation in theater with Ernest was another great opportunity. Ernest gave us insights into the transformation from the Shakespearean age to the current Broadway shows.

Our talk gave us a chance to trace the long history of transformation: man to woman, woman to man, which seems to be more prevalent recently, and I imagine it is because of the resurgence of women’s roles and power as we go forward in societal and cultural evolution.

In 2013, Ernest and Tisa Chang, Producing Director of Pan Asian Repertory Theater, invited me to choreograph their production of Dojoji: the Man Inside the Bell. It was written by Ernest, directed by Tisa, and included my performance. Actually, they were first inspired by my production of Dojoji 2002.

The Dojoji, the Archetypal Drama of Transformation

The Dojoji legends, concerning a woman and a bell, have been prevalent since the 11th century in the literature, dances, and dramas of Japan. The theme of a woman’s unrequited love has been popular across the world for centuries. Numerous works on this theme have been created: folk performances; the classical theater of Noh, Kabuki, and Kumi-odori; ballet; Flamenco dances; contemporary dramas such as the one by Yukio Mishima; numerous film productions; and even anime.

Most intriguing is the sequel version of the story, when the spirit of the woman returns to the Dojoji temple, where the story takes place in the world of imagination, symbolism, and fantasy. The epitome of this is the Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji (Maiden at the Dojoji Temple), first presented in 1753.

It is a goal for every classical dancer to perform Kyoganoko, as it requires mastery of techniques. In my early years as a classical dancer, I was focused on expressing “transformation” as a woman in various stages from the young to the old, as well as emotional changes from happiness to jealousy to anger.

However, looking back to Dojoji 2001 and 2002, which I choreographed after nearly 30 years of performing in America, it seems I wanted to create my own works, no matter how bold the idea of challenging a heritage and tradition hundreds of years old might be. At that time, I directed my focus to the universal human condition of attachment as a force of destruction.

After two decades now, I realize that we each possess the power of transforming ourselves. Amazingly, human history has proved that we have such power within us.

In the case of Dojoji, the power of transformation turned negative. But can we use this transformative power for a positive result? Can we water positive seeds in our subconsciousness to bring them to flower in our conscious minds as kindness and compassion?

Upcoming Chapter 7 will be about my works Dojoji 2001 and Dojoji 2002, the research prior to the productions, and collaborators.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!