SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: CHAPTER 10

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

The Cranes

“Yume (Dream), the closing piece for this program, is a remarkable signature piece for Ms. Ito’s dancing and acting. It is a poem in movement and truly shows the wide range of Ms. Ito’s knowledge and abilities.”

In Chapters 6 and 7, I explored the theme of transformation through dance. In Chapter 7, I discussed a transformation from a beautiful being into an ugly one: the lovely maiden turning into a hideous snake in the Dojoji story. But what about transformations going the other way, from the mundane to the ephemeral – like in a dream, where you trade your arms for wings and fly?

Birds hold a universal fascination for mankind. They are depicted in poetry, painting, and song across cultures. We watch them in their migrations, knowing as they fly overhead that the season is about to change. In the West, the official bird of October is the swan. In Japan, the birds that represent elegance and quintessential beauty are also waterfowl: the tsuru (crane) and sagi (heron). They are highly valued for their purity of color and the graceful sweep of their wings in flight. Another bird that is prevalent in Japanese art is the white-fronted goose, often depicted flying through the skies of autumnal paintings.

In the Kabuki dance Azuma Hakkei (The Eight Beauties in the East), geese become messengers of love when a character in the dance entrusts them with his love letter. What an enchanting idea it is! In another Kabuki dance, Fuji Musume (Wisteria Maiden), geese play an important role. At the end of the dance, the lyrics of the music describe the flight of the geese in the twilight sky:

空も霞の夕照りに

名残惜しむ帰る雁がねThe sky is hazy and the evening light is glowing,

the geese return home reluctantly.

We are left with a lovely and memorable image, an appropriate farewell to the end of the dance. The words “returning geese” make me wonder where they are going as I raise a hand to view them. Is this gesture a metaphor for two lovers returning to their home?

Hiroshige ukiyo-e painting in Omi Hakkei

As I child, I used to dream of flying. I was not transformed into a winged bird, but into Ten’nyo, the angelic figure depicted on the ceiling of Todai-ji Temple in Nara. There are many ways to analyze the psychology of flying dreams, but the only premise that resonates with me is that of freedom.

When I was young, I did not carry the pressures and worries that I do as an adult. My subconscious, unencumbered by responsibilities, must have taken flight very easily. Since then, I have loved “the flying in dancing,” whether classical, Kabuki dances, or my own works.

I choreographed flight in Chieko: The Element, the dance I created based on the work Chieko-sho (Collection of Poems for Chieko) by Kotaro Takamura. In one of the poems in the collection, “Lemon Elegy,” there is a line: “Chieko flies!” I had my singers sing this in a high-pitched voice, almost like an exclamation. In Chieko’s case, flying was a metaphor for leaping into a realm of insanity. I envisioned my own movements as that of a white bird, flying into the black space beyond the stage, the darkness of the theater becoming a spiritual world separated from reality. I believe that Kotaro wanted to express that Chieko found release from the worries and responsibilities she carried as a woman, wife, and artist in her flight. In doing so, he placed her on an eternal pedestal; in another poem, he expressed, “Chie-san, you are young forever.”

Other expressions of emancipation can be found in dances and plays in the genre of Kyoran-mono (the insanity pieces) in Kabuki plays, in which the protagonist loses his mind. My favorite is Onatsu Kyoran (Onatsu the Insane), the famous work created by Tsubouchi Shoyo in 1914. I performed it at Pace University Theater in 2004. This performance was a dream come true for me. Not only was I able to invite Shogo Fujima, a renowned dancer, to come to New York from Japan as a guest artist, but I was able to rent the exact same costumes from the original production from the Shochiku Kabuki Costume Shop.

While the portrayal of an insane character may suggest frenzy and ugliness in Western theater, in Japanese classical theater, an otherworldly, ephemeral beauty is a hallmark of insanity. I often think that we dancers are very fortunate to be able to transform ourselves into such characters.

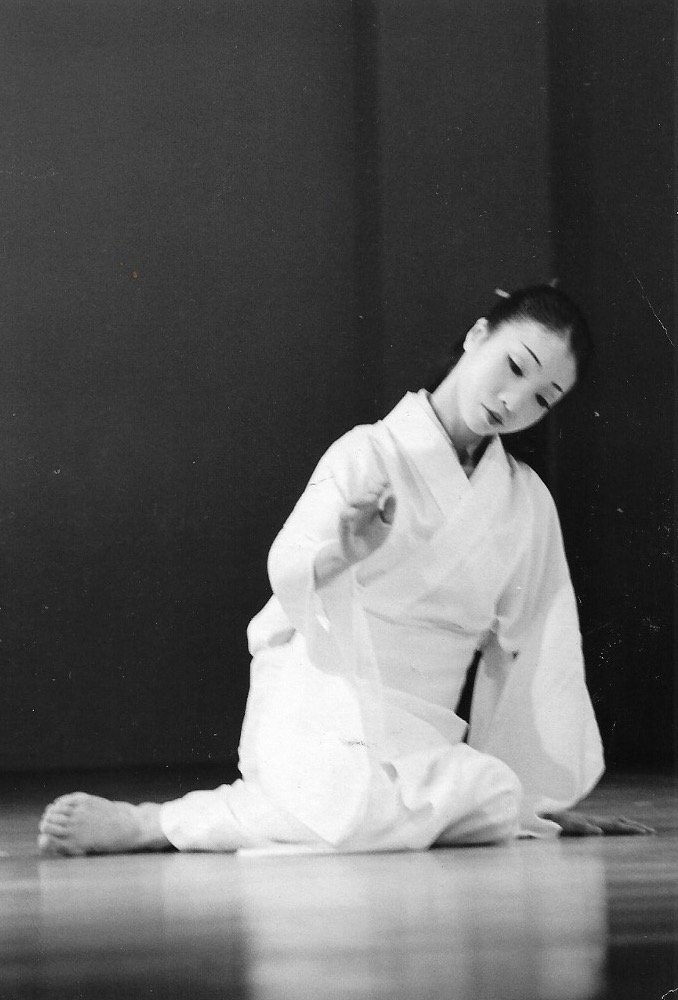

Sagi Musume (The Heron Maiden) at Mitsukoshi Theater, Tokyo

The first Kabuki dance I performed that was inspired by birds was Sagi Musume (The Heron Maiden) at Mitsukoshi Theater in Tokyo in 1968. Beloved from its first presentation in 1761, Sagi Musume has been recreated many times. The mystery of whether the heroine is a woman or a heron unfolds as she moves from joy to despair, before suffering her final fate in Hell. The white color of the heron suggests the innocence of a young lady before she experiences the turbulent emotions of a love affair, while the snow functions as a metaphor for both purity and the fleetingness of love as it melts away. The weight of the heroine’s thoughts is reflected in the heaviness of the snowfall, amplifying the drama of the Hell scene at the end, as the snow falls on the suffering heron. Since then, I have performed this piece numerous times in the U.S., and the long white sleeves and trailing hem of the costume have turned gray from brushing the floors of so many stages.

Performing Sagi Musume for Japan Society. Photo by Thomas Haar

My first original work with birds as a theme was Crane, which I presented at the 25th anniversary concert celebrating my American debut. This dance was inspired by one of my greatest supporter’s love for the red-crowned crane, one of Japan’s most beloved animals. I met Mary Griggs Burke at the celebration of her 75th birthday in 1991, which also commemorated her acquisition of a painting of a scene from Ibaraki, a well-known dance drama in Noh and Kabuki.

With Mrs. Burke at the post-performance reception of the 25th anniversary concert in 1997

The theme of the painting was a transformation of an old woman to a demon, so I created an infernal dance, accompanied by two dancers from my company. I had fractured my foot a few days before the performance, but knowing that the show must go on, I danced regardless and did not let anyone know of my injury until after the evening was over. You can imagine Mrs. Burke’s surprise when she found out after the party.

Crane. Photo by Kathy Sturgeon

Over the following years, Mrs. Burke’s support for my work was very important. After the 25th anniversary concert, held at Florence Gould Hall in 1997, she held a very special reception and tea ceremony at her residence for my guests.

Mrs. Burke was also a supporter of both the International Crane Foundation in the U.S. and the Japanese Crane Foundation. With her love of these beautiful birds combined with her love of Japanese art, she amassed a fabulous collection of screens depicting cranes from the Edo era, created by artists in the Rinpa school of painting.

When the International Crane Foundation in Wisconsin held a celebration for her 80th birthday in 1996, I was invited. I was thrilled to create another crane dance, this time based on the folktale Yuzuru (Twilight Crane). It was a magical evening. I had a special crane costume made with one white, sheer sleeve designed in the shape of a wing. In the story, the heroine first appears as a woman, although her true form is a crane. In the end, she returns to her avian form. I wanted to represent the character’s half-humanness to the audience with the sleeves’ one wing – to capture the essence of being caught between two worlds. The entire outdoor stage was dark but for a single bright streak of light. I felt as if I were entering a void in the darkness of that space, about to step into an infinite universe at the end of the dance.

Two decades later, in the installment of the Salon Series that introduced Japanese folk tales, I choreographed another Twilight Crane, accompanied by a flute and an ancient koto. Inspired by a Chinese Opera costume, I had the special sleeves designed as wings for my costume. I also invited a weaver to the program. After giving a demonstration of weaving on her loom, the same type used by the crane in the story, she became a part of the performance by being cast as a shadow. In the original tale, the crane, living as a human, secretly pulls out her feathers to make a beautiful fabric that her husband can sell in the market. I was very fortunate to be able to borrow the weaver’s piece of fabric to use as that woven by the crane. At the end of the piece, the wing-sleeves became large as I spread them, affecting a farewell gesture as the heroine departs the earth, abandoning her life as a human to return to her true form as a crane.

In 2008, I created a dance of cranes for a trio set to a modern koto composition by Sawai Tadao, Tori no Yohni (Just Like Birds), for dance students at Stephens College, where I was a visiting professor. These pieces were choreographed in a contemporary rather than a classical style. I was extremely happy with the result as the students, all trained ballet and modern dancers, performed so beautifully. It was also a lot of fun to go to local stores and choose fabric for costumes with the director of the costume department. I was very lucky to be invited to teach at a college that has such well-established and longstanding theater and dance departments. They make every effort to create the best college production possible and present them with great pride.

One of my most poignant performances came in October 2020. Salon Series No. 67: Prayer for Healing and Peace once more featured cranes as the central theme. In Japan, cranes are the symbol of longevity, healing, and happiness. Over the course of that spring and summer, we had watched the world come to a halt, overcome by disease. In spite of the pandemic, I decided to present the program. Of course, the circumstances of the lockdown necessitated that the performance had to be livestreamed, a first for my company.

As a prayer for the victims of COVID, I offered the dances Dedication, and Seiten no Tsuru (Cranes in the Blue Sky), performed by two of my dancers and me. The program also featured an origami demonstration by Colin McNally, whom I met during my Free Children’s Workshop program. Among the schools where I gave workshops in 2019 was the Beginning with Children Charter School in Brooklyn, where I taught Mr. McNally’s students. In 2020, hearing that he and his class had completed the senbazuru project, or one thousand folded paper cranes, I invited him to participate in the Salon Series program. Folding one thousand paper cranes has come to invoke well wishes of healing and recovery for those who are ill.

Mr. McNally was happy to talk about his senbazuru project for cancer survivors, and he showed us how to fold a paper crane. I also discussed twelve-year-old Sadako Sasaki, who famously set out to fold one thousand cranes after being diagnosed with leukemia as a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Her memorial at Hiroshima Peace Park is now covered with paper cranes from around the world. The program ended with my friend and guest artist Beth Griffith, a wonderful singer and actor, singing “Amazing Grace” as a light to guide our healing in the darkness of the pandemic.

Like the birds, we perform migrations of our own over the course of our lives – evolving from carefree dreamers to responsible adults who light the way for those who come after us. My journey began as my dream, then dancing as a crane, then evolving to a Salon Series, Prayers and Healing though Symbolism of Cranes. Was it a long flight, you might ask? Actually, it was a quick trip for seventy years – almost like being in a dream.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: Chapter 6

Photo by Heather Shroeder

This year renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

TRANSFORMATION

Ichikawa Shojo Kabuki (Ichikawa Girls’ Kabuki)

Greetings to June!

Welcome to the season of utmost beauty, heralded by shimmering light emanating through bright green leaves.

The Japanese have a word dedicated to this: komorebi, which means “sunlight leaking through leaves.” The transformation of glorious light to beautiful shadows dancing on the forest floor reminds me that transformation has been a central theme that runs not only through my work, but my life.

My training in professional performance (stage debut was in 1956) began in the late 1960s, when I joined the Ichikawa Joyu-za (Ichikawa Actresses Troupe) as a member of the chorus. The troupe was originally called Ichikawa Shojo Kabuki (Ichikawa Girls’ Kabuki).

Kabuki is known worldwide as an all-male theatrical discipline. However, in 1948, this all-female kabuki company was founded.

Ichikawa Shojo Kabuki was a sensational success during the early Showa Era (1926–1989) because the girls were phenomenally good actresses, playing both the male and female roles of the standard Kabuki plays. The company did not tour the mainstream stages, but rather local towns and city centers in various prefectures. Their acting, singing, and music in Gidayu was so good that the audience (including myself!) would often be driven to tears during the performance. As the years passed and the members of the troupe grew older, the name was changed to Ichikawa Joyu-za. The entire company—from the actresses, musicians, and singers to the stage crews and costume hands—were all female, with the exception of the choreographer. My impression of him was that he was very strict, as befitted one in our tradition. I was honored to join and gain valuable stage experience and learn the makeup and costuming.

Since the troupe gave performances at locations off the beaten path, the facilities were not as nice as they were in the big theaters. The backstage areas and dressing rooms in these old buildings could be quite drafty, which was difficult in the winter. I remember how cold it was to paint oshiroi, the white kabuki makeup, on my face and neck with a brush dipped in icy water. Touring with actresses whose whole lives, from childhood onward, twenty-four hours a day, were dedicated to performing, was a wildly different experience from what I had grown up with in the traditional Japanese dance circle. It taught me about what professionalism as an artist is.

Did their artistry of acting, of transforming into the characters’ personification of men, mean they were attempting to capture the other gender’s quality? I wondered if it is a human desire to act as the opposite sex. Eventually I realized that it was a different philosophy: They did not want to become the opposite sex, but to accomplish the transformation of their art and become whatever the character needed to be—male, female, somewhere in between, or without gender of any sort. I believe it was the human emotions, the suffering and love, that they did best to express through characterization. The universality, when and where (centuries ago/Japan), did not matter.

They were keen to listen to the choreographer’s critiques after each show and to dedicate themselves to improving for the next one. For them, acting was not just a desire for transformation, but their life, their breath, and their blood.

AIDS Fundraiser Performance

In the early 1980s, New York was poised on the eve of a great cultural shift, although I didn’t realize it at the time.

A career in the arts generally placed one in queer or queer-adjacent spaces, although the culture seemed to me to be more discreet than it is now. There was an exclusive club on East 51st Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues called Garden Club, or GH Club for short. The front door used to reveal a crowd of men in formal attire, dressed extremely well in suits and ties. A sense of pride prevailed in the club, and one sensed it was a privilege to be there. This was one of New York’s gay clubs. Although I was not one of them, I was allowed entry since I was a friend of the owner, Giro, my former dance student. The atmosphere was protected, safe, and the guests’ manners were graceful, gentle, and never vulgar.

Giro drank vodka; according to him he liked it as it does not smell of alcohol, which might be unpleasant to his patrons. That was one of his criteria of being a true “gentleman.” His mottos were “Be dressed well so that your partner, guests, or friends won’t be embarrassed at a gathering,” and “Be punctual; keep your appointments.” He hated those who broke them. I know when his finances dwindled down and he had no decent suits to wear, he borrowed formal attire like tuxedos from friends when the occasion called for it.

One day in 1983, Giro asked me to perform for an event at his club.

“Do you know AIDS? We are doing a fundraiser for it.” This was the first time I had ever heard of AIDS. It had only appeared in America in 1981 and wasn’t even called AIDS until late 1982. Even for some time afterwards, many of those around me had never heard of it, and widespread awareness would not happen for several years. So, the fundraiser held by Giro in 1983 was one of the first of its kind.

The event took place over several days. There was an artwork auction featuring works by Warhol, Vasarely, and Mapplethorpe, opened with a champagne reception. The main event was a brunch, which is when I performed. The event was a runaway success, and the club was so crowded that I had nowhere to dance except on top of the grand piano! I do not recall how much money Giro raised, but he was very pleased with the good result.

Giro was my friend for a decade, but we only used to meet a couple of times a year. Sometimes we would meet for tea at the Plaza Hotel—he took all of the nuts on our table upon leaving as a souvenir (!) although you can imagine how embarrassing it was to me, to behave thus while being surrounded by beautiful people. Another time we went for a drink at One if by Land, Two if by Sea, one of New York’s most storied restaurants. He would tell me that his boyfriend was a member of the Italian Mafia, and I would think it was a joke, but it might have been true. On one occasion, he entrusted me with several paintings, which I kept at my apartment. Several months later, I was asked to return them. That night, returning the artwork in a torrential rainstorm, was my last visit to the GH Club. The evening affair reminded me of a Jiuta-mai dance, in which there is a gesture of the heroine looking at her sleeve. This translates for a woman looking at the teardrops gathering on her sleeve, expressing sadness. I looked down and saw that my kimono and I were indeed wet. Afterward, I discarded the drenched kimono I was wearing, recognizing it as a kind of metaphor.

Many years later I bumped into him on the street right in Chelsea, where I had just moved. He told me he was staying with a friend whose entrance of the apartment building had a lovely spiral staircase, just around the corner. He invited my mother, who was visiting me then, and me to dinner, and I accepted his invitation. But remembering his drinking, which my mother noticed at one brief meeting we had had before, she declined the invitation. I believe he must have come to my building exactly at the appointed time. I haven’t seen him since.

Whenever I pass by an apartment with a spiral entrance on 23rd Street, although I am uncertain if that was where he stayed, I imagine he might appear, well-dressed as he used to be. Is he alive, well and happy? Or has he passed away?

Just a year ago, I noticed a Pride Flag held by the window of the apartment.

I only pray wherever he is, on earth or in heaven, that he is happy and enjoying his vodka.

Chieko and Dan

I have a dance titled under various names: Chieko, Chieko-sho (Chieko Anthology), Chieko Genso (Chieko the Element). The name has been changed with each new revision and presentation. Without the first presentation with Dan Erkkila, the composer, and the singers and actresses at Japan House in 1974, I would not have repeated and revised it so many times. This makes it sound like I was unhappy with Dan’s work, but it was quite the opposite: The music is so lovely that I keep coming up with new ideas and choreography for it.

Dan was a composer and flute player, who was introduced to me by Jean Erdman, the modern dance pioneer, who was a board member and supporter of my company for many years, and Teiji Ito, a great percussionist and improv musician. Teiji was the nephew of Michio Ito, another legendary modern dancer. Their great teamwork, often including Teiji’s wife, Cheryl, was an inspiration for me to produce works in my early days. We had fun performing together as an ensemble in such places as the Theater of the Open Eye, the YMCA at 53rd Street, and New York Botanical Garden. The last time I saw him was at Bellevue Hospital, where he was getting treatment for AIDS. Unfortunately, he succumbed to it in 1992. He was far too young to leave us without more of his beautiful music, one of the many bright talents whose lives were taken by this cruel disease.

I remember the time when he and his friend Steven allowed me to stay at their apartment on Bleecker Street while I was looking for my own place. On the walk downstairs from their fifth-floor apartment, the fragrance of baking bread from the Italian bakery on the first floor would reach me, and it was so inviting! The bakery was one of the oldest establishments in New York City. I never tasted it, since by the time I came home and was ready to buy bread for supper, the day’s bread was sold out – rumor had it, by noon! The 1970s and ‘80s were the good old days in the Village. It was a home to many artists, with Italian cafes with Italian paintings and old rugged couches, rusty gold-gilded espresso machines, and the most delightful espresso.

In Chieko, Dan’s ephemeral music intoned by the female chorus made it possible for me to leap into the world of Chieko. It was a place where you could play, a world beyond humanity, a world of insanity, a world of transparency. For this dance, I chose a white costume, a symbol of death, because it seemed there should be no reality, no color, no happiness or unhappiness. We did not have any set, no backdrop, just a simple spotlight in a few sections. I loved the spare space, the vacancy. While dancing, there was someone in white in the darkness.

Chieko. Photo by Ray Smith

It was only decades later that I was able to explore more of the world of “fantasy.” That was through the collaboration with Robert Lara at my series of performances called “Salon Series.” He introduced us to the world of Mexican mythology, bringing the world of a thousand years ago to life.

Fantasy and Illusion of Transformation in Theater and Dance

I was very fortunate to have Mr. Robert Lara accept the invitation to appear in my Salon Series No. 59, titled “Fantasy and Illusion of Transformation in Japanese Dance and Ballet,” in 2017. Mr. Lara, who heads the New York Baroque Company, was a soloist for the acclaimed Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo. Very graciously he offered to give a presentation of makeup used for him to become a queen of Mexican legend, and we all watched as his makeup artist demonstrated the application of makeup on him. He also discussed the transformation of genders in ballet and performed an excerpt from his work La Catrina. (La Catrina is a symbol for the Day of the Dead, Mexico's lady of death. She reminds us to enjoy life and embrace mortality.)

The large number of attendees we had showed keen interest in the subject of transformation. Perhaps in our daily lives we have an unnoticed desire in our subconsciousness to experience transformation for ourselves, as shown in the symbolism of Mexican mythology, which went beyond mere reversal of gender roles.

We had planned to give the second collaboration in June 2020 with a different theme, but unfortunately, it had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

My next exploration of transformation was with Ernest Abuba at Salon Series No. 69. Ernest was an actor, director, writer, and scholar with whom I had the honor of collaborating in several Off-Broadway productions, including Shogun Macbeth.

Transformation and Transition: Kabuki, Shakespeare, and Now

For a Japanese dancer, it is a joy to become the character of a Kabuki dance: the wisteria spirit in Wisteria Maiden, for instance, or the heron in Heron Maiden, tormented by unrequited love. I love dancing these roles.

Fuji Ondo (Wisteria Melody) from Fuji Musume (Wisteria Maiden)

Sagi Musume (Heron Maiden)

However, playing the role of a man is the one I find so interesting and fascinating, as well as a challenge. I particularly love Wankyu, the character from Sono Omokage Ninin Wankyu (Wankyu, the Two Shadows), a Kabuki dance first staged in 1774. In this story, the man who cannot live without the woman he loves goes mad. The music is superb and lyrical, and at one point it seems to be too fast a tempo to dance!

Up until 2021, I had only had the opportunity to perform this role once, at my recital at Japan House, inviting Sahomi Tachibana to dance with me in the role of Wankyu’s love, Matsuyama. Nonetheless, I used to practice the dance all the time, almost as a compulsion. In the summer of 2021, I was lucky enough to have a good young dancer as an intern and train her in the role of Matsuyama. The dance was presented at Salon Series No. 69.

Wankyu (Wanya Kyubei) in Salon Series No. 69. Photo by Heather Shroeder

During this presentation, we looked at transformation from various angles: from one gender to another, from the ordinary to the extraordinary. We also considered the transformation of actors and dancers in characterization through different times and places: from Shakespeare to Kabuki and from the sixteenth century to the present.

It was wonderful to dance Wankyu, but discussing transformation in theater with Ernest was another great opportunity. Ernest gave us insights into the transformation from the Shakespearean age to the current Broadway shows.

Our talk gave us a chance to trace the long history of transformation: man to woman, woman to man, which seems to be more prevalent recently, and I imagine it is because of the resurgence of women’s roles and power as we go forward in societal and cultural evolution.

In 2013, Ernest and Tisa Chang, Producing Director of Pan Asian Repertory Theater, invited me to choreograph their production of Dojoji: the Man Inside the Bell. It was written by Ernest, directed by Tisa, and included my performance. Actually, they were first inspired by my production of Dojoji 2002.

The Dojoji, the Archetypal Drama of Transformation

The Dojoji legends, concerning a woman and a bell, have been prevalent since the 11th century in the literature, dances, and dramas of Japan. The theme of a woman’s unrequited love has been popular across the world for centuries. Numerous works on this theme have been created: folk performances; the classical theater of Noh, Kabuki, and Kumi-odori; ballet; Flamenco dances; contemporary dramas such as the one by Yukio Mishima; numerous film productions; and even anime.

Most intriguing is the sequel version of the story, when the spirit of the woman returns to the Dojoji temple, where the story takes place in the world of imagination, symbolism, and fantasy. The epitome of this is the Kyoganoko Musume Dojoji (Maiden at the Dojoji Temple), first presented in 1753.

It is a goal for every classical dancer to perform Kyoganoko, as it requires mastery of techniques. In my early years as a classical dancer, I was focused on expressing “transformation” as a woman in various stages from the young to the old, as well as emotional changes from happiness to jealousy to anger.

However, looking back to Dojoji 2001 and 2002, which I choreographed after nearly 30 years of performing in America, it seems I wanted to create my own works, no matter how bold the idea of challenging a heritage and tradition hundreds of years old might be. At that time, I directed my focus to the universal human condition of attachment as a force of destruction.

After two decades now, I realize that we each possess the power of transforming ourselves. Amazingly, human history has proved that we have such power within us.

In the case of Dojoji, the power of transformation turned negative. But can we use this transformative power for a positive result? Can we water positive seeds in our subconsciousness to bring them to flower in our conscious minds as kindness and compassion?

Upcoming Chapter 7 will be about my works Dojoji 2001 and Dojoji 2002, the research prior to the productions, and collaborators.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!