Filmmaker Discusses the “Corky Factor” Behind “Photographic Justice”

Lee Young Kwok, better known by his childhood nickname, Corky, was a self-taught photojournalist who documented the everyday lives and struggles of members of the Asian American community in New York and beyond. Lee roamed the streets of Chinatown and practically every neighborhood in Manhattan, photographing everything from celebrations and festivals to protests and rallies in equal measure. Those who saw Lee’s work received a lesson in culture, history, and politics. There was Lunar New Year in Chinatown, a Yuri Kochiyama speech at a Japanese American Day of Remembrance program, a protest against police brutality that actually resulted in police brutality.

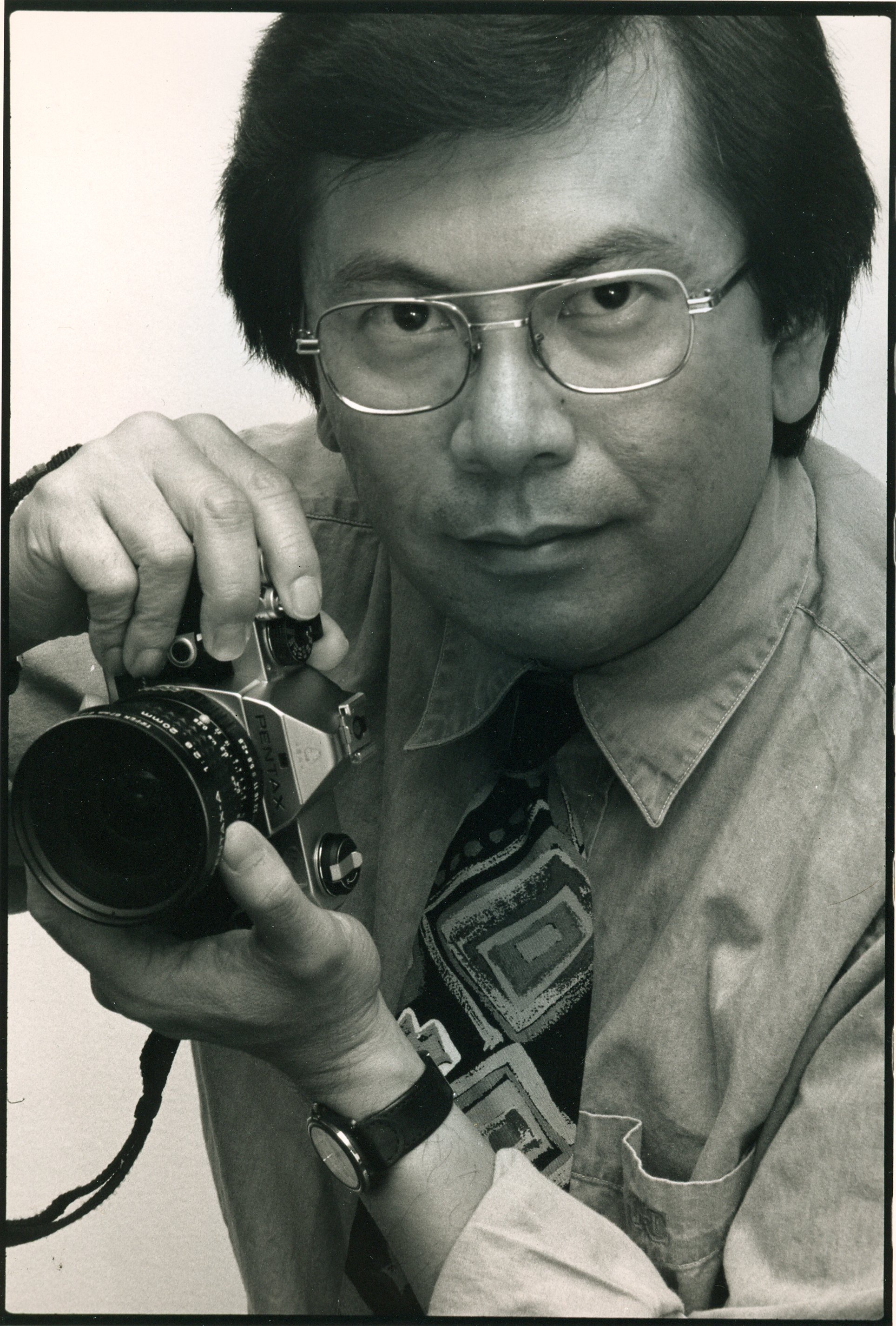

Photo Credit: Corky Lee

His photographs graced the pages of various publications, including The Village Voice, Downtown Express, The New York Post, and The New York Times. He had gallery exhibitions at institutions from New York to LA and places in between. Lee did this at a relentless pace for fifty years, until his death from COVID-19 in January 2021.

For almost twenty of those years, filmmaker Jennifer Takaki followed Lee with a camera of her own, documenting the documentarian. The result is the 2022 film Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story, which made the film festival circuit for more than a year and recently had a successful theatrical run at the DCTV Firehouse Cinema in New York as well as at theaters in LA. An edited version of the film premieres on PBS on Monday, May 13, presented by the Center for Asian American Media as part of the network’s Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

Takaki named her documentary after a phrase that Lee often used to describe his work. He would say, “I’m practicing photographic justice,” or declare that taking a certain picture was “an act of photographic justice.”

“It's the whole reason that Corky started his trajectory of his documentation of the AAPI community,” Takaki explains.

Takaki says that Lee coined the phrase in 2002, when he was interviewed by The New York Times after he recreated the historic 1869 Transcontinental Railroad photograph taken to commemorate the railroad’s completion in Utah. The original photographer excluded the Chinese laborers who helped build the railroad. In Lee’s recreation, he photographed the descendants of those Chinese men.

“I knew that that was a very pivotal moment. I knew it was a very pivotal photograph that, at that time, would have been the defining photograph,” Takaki says. “For me, [the phrase “photographic justice”] is a really important message because it's everything [about] why Corky does what he does. Which is why I started filming him anyway—to figure out why Corky does what he does.”

Photo Credit: Corky Lee

A chance encounter with Lee at an event led to Takaki’s curiosity about why the photographer spent all his free time photographing the community.

“He just showed me where the bathroom was and talked about the history of the building. I was like, ‘Who are you?’ And then he started to talk about everything he did,” Takaki says. “I started to follow him. I was going to do five-minute vignettes on people who had a singular focus. That's kind of what started me on my trajectory.”

With a background in television production, Takaki is no stranger to the camera and storytelling. She worked in news in Denver, Hong Kong, and New York, adding entertainment and corporate videos to her portfolio along the way. Lee introduced Takaki, a Japanese American, to fellow filmmaker and Japanese American Stann Nakazono. Together, the two formed an important community group known as ZAJA, where Japanese Americans network and support each other at monthly meetings held in the home of JA leader Julie Azuma. Lee was an honorary member from day one.

Filmmaker Jennifer Takaki. Photo Credit: All Is Well Pictures

During the nineteen years that Takaki followed Lee, she refined and distilled how she would present his story. Originally, the film’s ending was going to be one of the recreations of the Transcontinental Railroad photographs in Utah that Lee organized. Sadly, his death forced Takaki to add his funeral scene to the end instead.

But that is not the end of Corky Lee’s story. To Takaki, nearly two decades after starting the film, her work is just beginning. Photographic Justice has given her the opportunity to introduce Lee to audiences across the country, giving him a well-deserved moment in the spotlight, even in places where she believed Lee should have been popular already.

“What I was surprised about the most was that a lot of the AAPI communities did not know who Corky was,” Takaki says of the screenings she’s attended for the film. “We were just in Oregon, and . . . it was a sold-out show. I asked, ‘Who knew Corky?’ Only two people raised their hand. One of them happened to be from New York and literally knew Corky. I think that that's what surprises me. And that was an Asian American community; that was an Asian American event. I think that just shows that we have so much work to do. But I think it's also great that people are getting out to these events and seeing the film.”

Despite Lee’s relative anonymity outside of New York, Takaki has been pleased with the reaction to her film.

“I do think that it resonates with people and that they will forward it to people,” she says. “I also love the community—generally the filmmaking community—because I think everyone is so supportive of each other's films, and everyone wants to help each other get the word out. I always say it's the Corky Factor. You know there's that Corky Factor that makes people want to help. It's the reason that I have such a great group of people supporting me now. It's the reason that the film got finished. It's the reason the film's getting out. It's that Corky Factor that is undeniable. There is a Corky Factor to everything I do.”

Image Credit: All Is Well Pictures

The late-April theatrical release at DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema was particularly gratifying to Takaki. Ahead of the week of sold-out screenings with Q&A sessions, Takaki shared her excitement.

“There are so many things about it that are special. First of all, I have so much respect for [DCTV founders] Keiko and John Alpert. I love them. Also, they were comrades of Corky. They were so kind and generous to me during the whole time I worked on this film, showing so much support for it. Keiko watched the film, and she let me go through their archives. That’s just who they are as people, so that makes it special right there. But the fact that it's in Chinatown and that we will be having panelists who are part of Chinatown and part of the community and part of Corky’s story is so special.”

She wanted packed houses at DCTV, and New Yorkers delivered. But Takaki won’t be satisfied until Corky reaches superstar status. She has put pressure on herself and the community at large to “make sure we do Corky justice.”

“I want people to talk about Corky,” she says. “I want Corky to kind of become like Bruce Lee, you know? To be so synonymous, so outside of his own realm, that people know who he is, and he becomes a cultural figure, an icon in his own right. Because of what he means to so many. Because that whole pride, confidence, and sense of belonging that he brings such joy to anyone who had the pleasure of knowing him. Just his photos alone. If you know Corky, then you care about his photos. And then through that, you can learn the history of so many different peoples and communities.”

With Lee gone, the community lost not only a friend, but a large piece of coverage and advocacy is missing as well. Takaki thinks that people are continuing Lee’s legacy of photographic justice “in a diffused way,” but she places the onus on all of us to take up the mantle.

“When Corky was around, all you had to do was tell him that this was something important, and then he would show up,” Takaki says. “I don't know [everything that’s] going on in the AAPI community, but I do know that if you go to events and you don't see anyone taking photographs, then it becomes your responsibility to cover it.”

Takaki explains that the best place to start is to highlight and document community organizers and people who are doing good in the community. While there is no replacement for someone like Corky Lee, learning about his legacy and emulating his dedication can only help.

Photo Credit: Jennifer Takaki, All Is Well Pictures

If Lee were still alive, Takaki believes he would be documenting the meetings about and protests against the building of a new jail in Chinatown, something he had already started to do before his death. Of course, we would still see him at yearly community events, especially during May, AAPI Heritage Month.

Of the thousands of photographs Lee took, Takaki says her favorite is of a Sikh man who had wrapped the American flag around him at a candlelight vigil in Central Park following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

“Obviously, it's just such a beautiful image,” Takaki says. “I like Corky's explanation of people back on 9/11 who used the flag as protection [from discrimination]. It's such a beautiful and yet kind of sad but poignant photo.”

Indeed, the image is just one example of the many acts of photographic justice by Corky Lee.

Photo Credit: Corky Lee

Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story is available to watch for FREE on PBS Passport until Monday, June 10. To learn how to host a screening, please visit the film’s website and follow @corkyleestory and @wherescorkylee on Instagram and Facebook for updates.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!